Emotional Intelligence in the Political Sphere: Insights from the Core Emotion Framework

Political systems are deeply shaped by emotions and cognitive biases. This article delves into the Core Emotion Framework (CEF), a unique approach that categorizes fundamental emotional drivers into Head, Heart, and Gut centers. We demonstrate how CEF's ten core emotional processes offer a novel lens for understanding voter behavior, public sentiment, and leadership effectiveness, underpinned by robust academic research in neuroeconomics and political psychology. Explore how CEF can inform emotion-sensitive strategies for more resilient democratic systems.

Beyond Rationality: Leveraging the Core Emotion Framework for Political Insight and Action

How can we bridge the "rationality gap" in political analysis?

This article proposes the Core Emotion Framework (CEF) as a comprehensive solution, integrating its structured emotional processes with insights from behavioral economics and neuroeconomics. We detail how CEF's concepts, such as "Boosting" for motivation and "Constricting" for self-regulation, provide practical tools for political actors to enhance decision-making, resolve conflicts, and navigate complex public dynamics. Uncover the potential of an emotionally intelligent approach to political problem-solving.

The Core Emotion Framework: A New Paradigm for Political Understanding and Resolution

1. Introduction: The Emotional Landscape of Politics

The study of political behavior has long grappled with the complexities of human decision-making. Traditional political science has predominantly relied on the Rational Actor Theory, a foundational model positing that individuals function as rational agents. This theory assumes that individuals meticulously evaluate all available information and options to make choices that align with their predetermined goals and outcomes, ultimately maximizing their self-interest and utility1. Proponents of this view often characterize individuals as "all-seeing, objective thinkers" capable of logically connecting means to desired ends1.

However, the application of this normative approach frequently encounters challenges when attempting to explain real-world political phenomena. Empirical observations consistently reveal that human behavior often diverges significantly from purely logical or optimal choices1. This discrepancy creates a notable "rationality gap" in political analysis. This divergence is not merely a matter of occasional errors or unforeseen outcomes, as traditional models might suggest2, but rather stems from systematic and predictable influences of non-rational factors.

Critiques of the Rational Actor Theory highlight various limitations, including inherent individual cognitive constraints, the pervasive uncertainty of real-world environments, and the complexities introduced by principal-agent problems in implementation2. Furthermore, this model tends to downplay the profound influence of emotions, cultural norms, social pressures, and even seemingly irrational behaviors on political decisions4. Consequently, a comprehensive framework that explicitly incorporates these emotional and non-rational elements becomes not just an alternative perspective, but an essential complement to conventional political analysis, offering a more descriptively accurate and robust understanding of political phenomena.

In recent decades, there has been a growing recognition of the significant role emotions play in shaping political behavior. Fields such as behavioral economics have emerged, combining principles from economics and psychology to empirically demonstrate that individuals do not always make what neoclassical economists consider "rational" or "optimal" decisions, even when equipped with complete information and necessary tools3. This discipline, significantly influenced by scholars like Richard Thaler, characterizes human beings as entities susceptible to emotion and impulsivity, whose choices are profoundly influenced by their environments and circumstances3.

Early critiques of rational choice might have labeled deviations from rationality as simply "irrational"1. However, the advancements in behavioral economics and neuroeconomics have shown that these deviations are frequently predictable1. This shift in understanding, from viewing human behavior as "irrational" to recognizing it as "predictably biased" or "emotionally influenced," is crucial. If emotional influences are indeed predictable, they can be systematically studied, understood, and potentially leveraged or mitigated in political contexts, moving beyond mere observation to informed intervention and strategic design.

Further deepening this understanding, the interdisciplinary field of neuroeconomics bridges neuroscience, psychology, and economics. It offers an unparalleled perspective into how neural mechanisms, encompassing both emotional responses and cognitive processes, profoundly influence decision-making at individual and collective levels5. Neuroeconomics helps elucidate why political strategies sometimes defy expected norms and why voters make specific choices, by examining the brain's integration of information and value judgments under uncertainty6.

Within this evolving landscape, the Core Emotion Framework (CEF) presents a novel and systematic approach to understanding emotional dynamics. It is described as a hierarchical model of foundational emotional drivers, organized into a tripartite structure: Head, Heart, and Gut7. The CEF posits that these core emotions are the "root of every action and reaction" and can be "harnessed" as powers rather than merely problems to be solved7. Unlike many existing theories that primarily describe the impact of emotions, the CEF provides a structured vocabulary of specific emotional processes and even proposes "cycling points" for their intentional activation7. This moves beyond abstract emotional concepts to concrete "mental operations"7.

This actionable nature of the CEF suggests it could provide political actors—including leaders, policymakers, and citizens—with a practical toolkit for enhancing self-awareness, emotional regulation, and strategic engagement within the political sphere, thereby fostering greater emotional agility7.

This article will argue that by integrating the Core Emotion Framework with established academic research in political psychology, behavioral economics, and neuroeconomics, a more profound and actionable understanding of political decision-making, public opinion, leadership, and conflict resolution can be achieved. This integration offers promising pathways for more effective governance and civic engagement in an increasingly complex world.

2. The Core Emotion Framework: A Foundation for Understanding

The Core Emotion Framework (CEF) provides a structured lens through which to understand the multifaceted nature of human emotions and their influence on behavior. This framework is built upon a tripartite structure, drawing an analogy to the Head, Heart, and Gut, each representing distinct yet interconnected facets of emotional processing and response7.

2.1. Tripartite Structure: Head, Heart, and Gut

The Head is positioned at the top of this hierarchy, representing cognitive and analytical functions7. This domain encompasses how individuals perceive, analyze, and make choices based on processed information8. It includes core emotional elements that enable rational thought, deliberate decision-making, and intellectual processing, serving as the basis for more complex mental integrations7. Head emotions are considered the architects of perception, analysis, and choices, shaping how information is processed and how the world is experienced7. This cognitive center aligns strongly with the cognitive component of the three-component model of emotion, which posits that thoughts and interpretations of situations significantly influence emotional experiences7.

The Heart occupies the central tier, capturing the affective and relational dynamics of human experience7. This realm emphasizes an individual's capacity for empathy, introspection, and the management of social dynamics8. It houses elemental core emotions that drive empathy, connection, and intrinsic emotional awareness, forming the foundation for deeper affective responses7. Heart emotions are intricately associated with the innate capacity for openness, profound connection, genuine empathy, and the essential skill of setting healthy boundaries7. This aspect of CEF resonates with the relational or social component of the three-component model of emotion, emphasizing the role of emotions in interactions with others8.

At the foundational level, the Gut embodies instinctual, embodied, and action-oriented responses7. This center governs the emotions that propel individuals forward, provide a sense of satisfaction, and signal the need for rest and recovery8. These powerful emotions are the wellspring of productivity, deep engagement, and the vital impetus for action, encompassing both vigorous goal pursuit and the essential need for recovery and replenishment7. The Gut aspect of CEF aligns with the behavioral component of the three-component model of emotion, highlighting the direct link between emotions and actions and motivations8.

Traditional models often separate cognition from emotion, treating them as distinct entities. However, the CEF's tripartite model explicitly integrates these domains, suggesting that political behavior is a synergistic outcome of cognitive processing ("Head"), relational and social dynamics ("Heart"), and motivational drives ("Gut")7. This offers a more holistic map for understanding political phenomena than fragmented psychological constructs. When analyzing political issues, this integrated structure encourages a multi-dimensional assessment. This means considering not only the logical coherence of policy proposals (Head), but also the underlying public sentiment and intergroup relations (Heart), and the collective drive for action or resistance (Gut). This comprehensive approach can lead to the development of more nuanced and effective political strategies.

2.2. The Ten Core Emotional Processes: Definitions, Functions, and Benefits

Within this tripartite structure, the CEF meticulously delineates ten core emotional processes. These are strategically categorized across the Head, Heart, and Gut centers and are described as dynamic, actionable processes designed for quick comprehension and immediate, real-world application7.

- Head Emotions (Cognition and Decision-Making)

- Sensing (-outgoing): This is defined as the initial stage of perception, where individuals actively gather information from their internal and external environments with heightened awareness7. Its proposed function is to foster adaptability and significantly enhance the ability to gather crucial, unfiltered information, forming the foundation upon which subsequent cognitive and emotional processing occurs7. A stated benefit is improved perceptual clarity, which can be cultivated through mindfulness practices7.

- Calculating (-reflecting): This process involves an in-depth analysis and evaluation of sensed information, characterized by rigorous logical processing, critical thinking, and the assessment of gathered information in relation to existing knowledge and beliefs7. It is vital for sophisticated problem-solving and strategic planning, as individuals reflect on the implications and potential outcomes associated with different pieces of information7. Benefits include enhanced strategic thinking and problem-solving abilities8.

- Deciding (-balancing): This is the culminating skill of making balanced, informed choices and firmly committing to a chosen course of action7. It involves weighing different options, considering potential consequences, and ultimately selecting a path that deeply aligns with personal values and goals7. This emotion is considered the linchpin for agency, self-efficacy, and purposeful direction, allowing movement from contemplation to concrete action7. Benefits include improved leadership effectiveness through confident and balanced decision-making8.

- Heart Emotions (Connection and Emotional Flow)

- Expanding (-outgoing): This emotion describes feelings associated with openness, connection, and empathy towards others, fostering positive relationships and facilitating collaboration7. It encourages boundless creativity, personal growth, and critical adaptability in a rapidly changing world7. Benefits include improved teamwork, enhanced empathy towards colleagues, and a willingness to explore new ideas7.

- Constricting (-reflecting): This focuses on inward-directed feelings such as introspection, setting healthy boundaries, and mindful focus on personal needs and deep self-reflection7. Its proposed function involves a vital internal examination and refinement of personal understanding and priorities, preventing burnout and ensuring needs are met amidst external demands7. Benefits include helping individuals manage anxieties related to performance and maintaining emotional well-being7.

-

Achieving (-balancing): This encompasses the emotions involved in navigating social interactions, managing relationships, and adapting to the complexities of social dynamics, while relentlessly striving for and attaining success7. This emotion fosters unwavering perseverance and remarkable adaptability, especially in complex and demanding situations7. Benefits include enhanced client relations, improved negotiation skills, and the ability to break down larger goals into manageable steps for sustained progress7.

- Gut Emotions (Action and Motivation)

- Arranging (-outgoing): This describes emotions linked to organization, taking decisive control of situations, and initiating purposeful action towards goals with a strong sense of agency7. Its proposed function is to drive proactive coping mechanisms and cultivate profound resourcefulness, empowering one to shape their environment and circumstances7. A benefit is facilitating stress and workload management by promoting organization and a sense of control8.

- Appreciating (-reflecting): This vital capacity focuses on feelings of satisfaction, gratitude, and the positive reinforcement derived from accomplishments and experiences7. It is a potent force that builds sustained motivation and reinforces self-efficacy, creating a positive feedback loop for future endeavors7. Benefits include enhancing overall life satisfaction and cultivating a resilient mindset7.

- Boosting (-balancing in "on" mode): This encompasses the energizing emotions that drive individuals towards their objectives, representing a state of heightened motivation, enthusiasm, and a focused drive to overcome challenges and achieve success7. It significantly enhances endurance and builds formidable resilience7. Benefits include providing necessary motivation and energy for challenging projects, igniting enthusiasm for learning, and promoting perseverance7.

- Accepting (-balancing in "off" mode): This profound capacity describes the emotions associated with letting go, accepting limitations, and recognizing the need for rest and recovery.7 Its proposed function involves acknowledging when to disengage, allowing oneself to recharge, and accepting situations that are beyond one's control.7 This emotion fosters deep emotional flexibility, remarkable adaptability, and a powerful alignment with one's true purpose.7 Benefits include preventing burnout, promoting sustainable performance, and cultivating trust in the natural unfolding of events.7

While each of these ten emotions possesses a distinct definition and function, the CEF emphasizes their dynamic interplay and "adaptive emotional cycling"7. For instance, engaging in intense "Boosting" (motivation) without incorporating sufficient "Accepting" (rest and recovery) can lead to burnout8. This suggests that political effectiveness is not about maximizing a single emotion, but rather about skillfully cycling through these emotional states. This understanding indicates that political leaders and citizens need not only to comprehend individual emotional states but also to cultivate the ability to fluidly transition between them.

For example, a period of intense "Boosting" during a political campaign must be followed by "Accepting" for recovery to prevent exhaustion, thereby ensuring long-term political sustainability and personal well-being. This perspective points towards a dynamic model of political leadership and engagement, emphasizing adaptability and emotional balance.

3. Bridging Emotion and Political Cognition: Overlapping Academic Research

The Core Emotion Framework finds significant corroboration and expands upon existing academic research in political psychology, behavioral economics, and neuroeconomics. These fields collectively challenge the limitations of purely rational models and illuminate the profound influence of emotions and cognitive biases on political behavior.

3.1. Critiques of Rationality and the Rise of Behavioral Approaches in Politics

Behavioral economics fundamentally challenges the "homo economicus" assumption of perfect rationality, which posits that individuals always make optimal, self-interested decisions1. Instead, this field highlights systematic deviations from rational judgment, known as cognitive biases, which significantly shape public opinion and decision-making within the political sphere9.

One prominent example is Confirmation Bias, the pervasive tendency to seek, interpret, favor, and recall information in a manner that confirms one's pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses9. In politics, this bias manifests in various ways, such as individuals selectively consuming news sources that align with their political views, interpreting data to support preconceived notions, or disregarding contradictory information9. This contributes to increased polarization, the spread of misinformation, and the formation of echo chambers, making critical thinking and the design of well-informed policy considerably more difficult9. Political actors and media frequently exploit this bias to manipulate public opinion10.

Another significant cognitive bias is Anchoring Bias, which refers to the tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information encountered (the "anchor") when making a decision, even if that information is irrelevant or unreliable.9 In political contexts, this can influence outcomes in budget negotiations, treaty discussions, and policy debates, where initial proposals or reference points can disproportionately shape subsequent discussions and final agreements.9

Prospect Theory offers further insights by explaining how individuals' attitudes toward risk are not constant but depend on whether they perceive themselves to be facing potential losses or gains3. This theory posits that people tend to be risk-averse when confronting gains, preferring a sure win over a gamble with a higher potential payoff but also a risk of losing everything.

Conversely, they become risk-accepting when facing losses, often taking greater risks to avoid a certain loss11. This contrasts sharply with traditional rational choice theories, which typically assume choices are based on end states and a general risk aversion11. Research suggests that political behavior may be even more susceptible to these decision biases and fallacies than market behavior11.

The Affect Heuristic describes how individuals often rely on their emotions, rather than concrete information, to make quick judgments12. While this allows for rapid conclusions, it can distort thinking, leading to suboptimal choices, and significantly influence risk perception12. This heuristic is a product of "System 1" thinking, an automatic, intuitive cognitive process12.

These biases are further illuminated by Dual-Process Theories, which propose that human decision-making involves two distinct cognitive systems: a fast, intuitive, automatic "Type 1" system that relies on prior knowledge and heuristics, and a slower, reflective, effortful "Type 2" system12. The affect heuristic is a prime example of System 1 thinking12. Research suggests that strongly held political beliefs can make it difficult for individuals to engage their Type 2 logical reasoning system, particularly when confronted with opposing political views. For instance, some studies indicate that political conservatives may have more difficulty inhibiting their fast political knowledge system to employ slow logical reasoning in the context of political information, whereas liberals may exhibit a more flexible cognitive style14.

The pervasive nature of cognitive biases and System 1 thinking in politics frequently leads to outcomes that deviate from pure rationality1. The CEF's emphasis on "Calculating," which involves logical processing and critical thinking7, directly addresses the need for engaging Type 2 reasoning. Its focus on "Sensing," which involves actively gathering unfiltered information7, can help counteract the tendency towards selective exposure inherent in confirmation bias9.

By intentionally cultivating "Calculating" and "Sensing," political actors can actively work to mitigate the impact of biases like confirmation bias and anchoring, thereby fostering more evidence-based policy-making9. Furthermore, understanding the affect heuristic and prospect theory through the CEF's lens allows for the development of strategic communication approaches that acknowledge and account for emotional responses without solely relying on manipulative tactics11. This approach moves beyond simply identifying biases to providing a framework for actively managing and responding to them.

3.2. The Neurobiological Underpinnings of Political Decision-Making

Neuroeconomics offers an unparalleled perspective into how neural mechanisms influence decision-making processes on both individual and collective levels6. It helps explain why individuals often deviate from classical economic rationality and why certain political strategies sometimes defy expected norms, by providing cognitive insights into how the human brain integrates information and value judgments6.

The Somatic Marker Hypothesis, formulated by Antonio Damasio, proposes that emotional processes, specifically "somatic markers"—feelings in the body associated with emotions—guide or bias behavior, particularly in complex and uncertain situations16. These markers, such as a rapid heartbeat signaling anxiety or nausea signaling disgust, are thought to be processed in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and the amygdala16. This hypothesis directly challenges economic theories that model human decision-making as being devoid of emotions and based solely on logical cost-benefit calculations, asserting that emotions play a critical role in the ability to make fast, rational decisions16.

Mapping CEF's "Head" Emotions to Neural Correlates

- Sensing: The CEF defines "Sensing" as the primal capacity to perceive and interpret internal and external stimuli with heightened awareness, actively gathering unfiltered information7. Neuroscientifically, "Sensing" is strongly linked to the insula cortex7. This brain region is crucial for processing interoceptive signals—internal bodily sensations such as heart rate, breathing, or the sensation of "butterflies in your stomach"17. The insula plays a central role in integrating sensory, emotional, and cognitive information, and is considered vital for emotional awareness and decision-making17.

The connection between CEF's "Sensing" and the insula highlights the embodied nature of political intuition. This provides a neurobiological basis for what are often colloquially referred to as "gut feelings" in political contexts17. These intuitions, often dismissed as irrational, are in fact rapid, integrated assessments of complex information, influenced by the body's physiological state16.

Political leaders and voters may unconsciously rely on these somatic markers when making quick judgments, especially under conditions of uncertainty16. Cultivating "Sensing" through practices like mindfulness, as suggested by CEF7, could enhance a political actor's ability to consciously interpret these internal signals, potentially leading to more informed and less biased "intuitive" political judgments. This also suggests that public policy narratives that resonate with visceral feelings might be more effective in influencing public opinion15.

- Calculating: This CEF emotion involves in-depth analysis, rigorous logical processing, and critical thinking7. This aligns significantly with the concept of executive functions (EF), which are considered critical skills for effective political leadership and decision-making22. The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is recognized as the critical brain site for executive function, involved in cognitive control, problem-solving, and strategic planning22. Research distinguishes between "cool EF," which operates in neutral, non-affective situations, primarily linked to the lateral PFC and posterior parietal cortex, and "hot EF," which functions under affective conditions and involves the lateral PFC and the brain's reward system24.

The correspondence between CEF's "Calculating" and cognitive control and executive functions is clear23. The distinction between "cool" (logical, pure Calculating) and "hot" (affective, Calculating fused with Sensing and Deciding) executive functions is particularly critical in politics, where decisions are rarely made in a purely detached, "cool" environment; they are often made under intense emotional pressure or carry significant emotional stakes24. Effective political strategy, therefore, requires not just logical analysis ("cool Calculating") but also the ability to reason and make sound decisions even when emotions run high ("hot Calculating"). Training political leaders to enhance "Calculating" needs to encompass both aspects, enabling them to maintain composure and critical thinking even amidst emotional turmoil, or to strategically leverage "hot" cognition when appropriate for persuasive communication or motivational purposes.

-

Deciding: This CEF emotion represents the culminating skill of making balanced, informed choices and firmly committing to a chosen course of action7. This process is intrinsically linked to dopamine pathways in the brain, which are critical for motivation, reward prediction, and reinforcing goal-directed behavior5. The mesolimbic dopamine system, comprising the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the nucleus accumbens (NAc), is a key detector of rewarding stimuli and a crucial determinant of motivation and incentive drive25.

CEF's "Deciding" is fundamentally about commitment and action7. The connection to dopamine pathways implies that successful political decisions, even seemingly minor ones, activate the brain's reward system, thereby reinforcing the behavior of decisiveness itself25. This creates a positive feedback loop, where successful decision-making fosters a greater propensity for future decisive action7. Conversely, perceived failures or a lack of anticipated reward can inhibit future decisiveness, leading to decision paralysis. To foster decisiveness in political leaders, strategies could involve breaking down complex policy goals into smaller, achievable "wins"7. This approach can trigger dopamine release and reinforce the act of deciding, building a "small win" momentum28 that counteracts the decision paralysis often observed in complex political environments, ultimately boosting self-efficacy7.

Mapping CEF's "Heart" Emotions to Neural Correlates

- Expanding: This CEF emotion embodies openness, connection, and empathy7. Neuroscientifically, this activates creativity networks in the brain, such as the Default Mode Network (DMN) and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), which are involved in generating novel ideas7. Furthermore, it engages empathy networks, including the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and fronto-insular cortex29. Empathy, a cornerstone of human social interactions30, is partly based on shared neural representations, meaning that observing distress or joy in others activates similar brain regions as if one were experiencing it firsthand29.

The importance of "Expanding" for empathy is clear, as empathy is crucial for social cohesion30. The neural basis of empathy, involving shared representations in areas like the ACC, suggests that understanding others' political distress or joy involves activating similar brain regions as if one were experiencing these emotions themselves29. This directly challenges the "us vs. them" mindset prevalent in political polarization4. Cultivating "Expanding" in political discourse can thus move beyond mere intellectual understanding to a deeper, embodied empathy, potentially bridging ideological divides by fostering shared emotional experiences. This offers a powerful tool in conflict resolution and promoting bipartisan cooperation7.

- Constricting: This emotion represents introspection, the setting of healthy boundaries, and mindful focus on personal needs and deep self-reflection. Generally, it is highly important for anyone in political or personal agenda to acknowledge a "stop" sign, as well as a red light or line7. Neuroscientifically, "Constricting" engages the calm response system, aligning with the Polyvagal Theory's ventral vagal pathway7. This pathway promotes feelings of safety, dampens fight-or-flight responses, and is crucial for emotional intelligence and self-regulation7.

In highly demanding and often toxic political environments, the ability to "Constrict" and set boundaries is vital for continues success and to prevent burnout7. The Polyvagal Theory provides a neurobiological explanation for how this inward focus activates calming systems, indicating that this is not merely about disengagement but about strategic self-preservation33. Political actors, constantly exposed to stress and conflict, can intentionally activate "Constricting" to maintain emotional well-being and sustained effectiveness7. This also suggests that a healthy political system benefits from mechanisms that allow individuals to "disengage" and "recharge" without being perceived as weak, thereby promoting psychological flexibility35.

- Achieving: This dynamic emotion represents the ability to appear presentfully in public, and to effectively balance multiple tasks, roles, and responsibilities while relentlessly striving for and attaining success7. This fuels sustained effort and goal-oriented action by activating the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, particularly the dorsal striatum7. This pathway is known to encode motivation, habit formation, and task persistence28.

CEF's "Achieving" directly maps to concepts of "grit" and persistence, which are essential for long-term success28. The activation of the dorsal striatum and mesolimbic dopamine pathway highlights the biological underpinnings of sustained effort in the face of political challenges28. This is not just about initial motivation but the endurance required for achieving long-term political goals. Understanding this neurobiological basis allows for the development of strategies to cultivate political "grit," such as breaking down large objectives into smaller, reinforcing tasks7. This can help political movements or leaders maintain momentum and overcome the inherent arduousness of the political journey, reinforcing the drive for continuous progress.

Mapping CEF's "Gut" Emotions to Neural Correlates

-

Arranging: This CEF emotion signifies the proactive ability to take decisive control of situations, organize resources, and initiate purposeful action towards goals with a strong sense of agency7. This involves cognitive processes supported by the parietal lobe7. The parietal lobe is implicated in spatial processing, mental rotation, and recognizing relationships between mental representations—all crucial for imposing order and reducing cognitive load37.

"Arranging" in politics involves the complex task of organizing campaigns, policies, or movements. The link to the parietal lobe, which is responsible for spatial organization and integrating sensory input to represent the world, suggests that effective political organization relies on fundamental cognitive processes of imposing order on complex information37. Enhancing "Arranging" in political contexts could involve training in structured planning, visualization of complex systems, and resource allocation, leveraging the parietal lobe's role in creating order from chaos7. This highlights that even seemingly abstract political organization has a concrete cognitive basis, rooted in the brain's capacity for spatial and logical structuring.

-

Appreciating: This vital capacity involves celebrating achievements, acknowledging progress, and experiencing profound feelings of satisfaction and gratitude7. This process triggers the release of serotonin and dopamine, neurotransmitters associated with improved mood, cognitive function, and overall well-being7. It serves as a potent force that builds sustained motivation and reinforces self-efficacy7.

In highly adversarial political environments, a common tendency is to focus on negatives, contributing to polarization4. "Appreciating" actively counteracts this by releasing positive neurochemicals and effectively "rewiring the brain" to focus on positive aspects7. This can combat the "hedonic treadmill" in politics, where successes are quickly taken for granted and the focus shifts to the next problem. Encouraging "Appreciating" within political movements or among citizens can build collective resilience and foster a more positive outlook, counteracting the negative emotional effects of setbacks7. This suggests a powerful tool for fostering a more constructive political culture, moving away from constant criticism towards acknowledging shared progress and building a sense of collective accomplishment.

- Boosting: This dynamic emotion represents the ability to energize and sustain effort, uplifting oneself and others7. It is linked to self-belief, motivation, and resilience7. Imagining one's "Best Possible Self" has been shown to improve positive expectations and mood7.

"Boosting" is fundamentally about generating internal power and self-belief7. The connection to reshaping cognitive biases towards optimism suggests a self-fulfilling prophecy mechanism: believing in success and actively pushing it (through "Boosting") can enhance motivation and perseverance, thereby making success more likely7. Political leaders and movements can intentionally cultivate "Boosting" to inspire their base, enhance collective efficacy, and maintain momentum, especially during challenging times. This involves not just external rhetoric but the internal cultivation of self-belief and positive expectations, which has a tangible neurobiological basis7.

- Accepting: This profound capacity involves the ability to let go of control, accept current reality, and recognize the need for rest and recovery7. It fosters deep emotional flexibility and remarkable adaptability7. Neuroscientifically, "Accepting" reduces stress reactivity, a principle rooted in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and mindfulness7. It helps individuals avoid rumination and engage constructively with challenging realities7.

In a rapidly changing and often unpredictable political landscape, the ability to "Accept" reality without resistance is crucial. This aligns with psychological acceptance and stress regulation, allowing political actors to disengage from unproductive struggle and adapt, rather than rigidly clinging to outdated strategies35. Promoting "Accepting" within political leadership can prevent burnout and foster resilience7. It encourages a more pragmatic and flexible approach to policy, allowing for learning from failures and adapting to new information, rather than being paralyzed by rigid adherence to a "perfect" plan. This also has profound implications for managing public disappointment and fostering collective resilience in the face of political setbacks, contributing to a more adaptable and sustainable political system.

4. CEF in Political Problem-Solving and Enhanced Understanding

The Core Emotion Framework offers a practical and structured approach to addressing complex political questions, moving beyond theoretical understanding to actionable strategies. By integrating its principles, political actors can enhance decision-making, foster intergroup relations, navigate public opinion, and promote overall political resilience.

4.1. Enhancing Political Decision-Making

By cultivating the "Sensing," "Calculating," and "Deciding" emotions, political actors can significantly improve their capacity for effective decision-making. This involves gathering more accurate, unfiltered information through enhanced "Sensing"7, analyzing it logically and critically via "Calculating"7, and ultimately making balanced, informed choices through "Deciding"7. This approach moves beyond the impulsive or biased decisions often observed when relying solely on traditional rational models1. The framework encourages a structured analytical process7 that can help leaders weigh options and commit firmly to a course of action, even when faced with incomplete information7. This directly addresses the limitations of purely rational models by integrating emotional intelligence into the decision process, recognizing that effective leadership requires both cognitive and emotional competencies45.

Political decision-making is frequently reactive, driven by immediate threats or opportunities15, which the CEF views as an interaction by the Arranging core emotion (accompanied by and fused with Achieving and Boosting), to manipulate the Head building blocks. However, by intentionally cultivating CEF's Head emotions individually, political actors can shift from reactive, heuristic-driven choices12 to more proactive, deliberative, and values-aligned decisions7. This suggests that training in CEF could equip political leaders to better navigate crises, anticipate consequences, and make choices that are both strategically sound and deeply aligned with their stated values. Such an enhancement in decision-making capacity can significantly contribute to increased public trust and overall policy effectiveness.

4.2. Fostering Intergroup Relations and Conflict Resolution

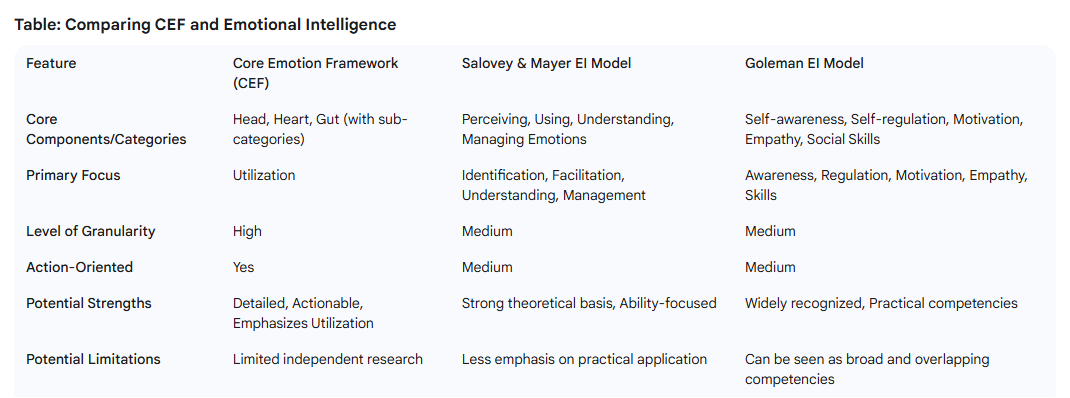

Emotional intelligence (EI), encompassing self-awareness, self-regulation, empathy, and social competence31, is widely recognized as crucial for effective political leadership and conflict resolution32. The CEF provides a granular vocabulary for these essential EI components, offering specific emotional processes that can be successfully cultivated7.

The application of CEF's "Heart" emotions is particularly relevant in this domain:

-

Expanding cultivates genuine empathy and profound connection7. This directly counters the "us vs. them" mindset that often fuels political polarization (-Arranging)4. It promotes open-minded discussions and encourages individuals to understand diverse viewpoints without judgment7.

- Constricting enables the establishment of healthy boundaries7, which is crucial for managing emotional intensity in conflicts and preventing burnout in demanding interpersonal dynamics32.

- Achieving involves effectively balancing multiple social roles and navigating complex social interactions7, fostering perseverance and adaptability in difficult relational dynamics7. Research indicates a positive correlation between high levels of emotional intelligence and an "integrating style" of conflict handling, which is generally considered the most effective approach31.

Political polarization poses a significant threat to democratic institutions and social cohesion4. CEF's Heart emotions directly address the psychological mechanisms underlying this division. "Expanding" fosters empathy, breaking down in-group favoritism and promoting a broader sense of shared humanity4. "Constricting" allows for self-preservation amidst conflict, preventing complete disengagement or overly reactive responses32. "Achieving" promotes collaborative problem-solving and the ability to navigate complex social demands32.

Implementing CEF-based emotional literacy programs for political actors and citizens could provide concrete strategies to bridge divides, foster mutual understanding, and move towards more harmonious and sustainable political outcomes7. This approach shifts the focus from merely diagnosing polarization to actively intervening with practical emotional competencies.

4.3. Navigating Political Dynamics and Public Opinion

Emotions profoundly influence public policy and voter behavior15. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for effective political engagement.

Emotional Contagion demonstrates that emotional states can be transferred between individuals, even without direct interaction or nonverbal cues, as evidenced in large-scale social networks49. Politicians' emotional displays can be highly persuasive, though their effect often depends on whether the audience perceives them as belonging to an in-group or an out-group47. For example, happy displays from in-party politicians tend to elicit congruent facial activity in supporters, while out-party politicians may elicit a reactive or even opposite emotional response47.

Framing Effects illustrate how political communications, by emphasizing certain characteristics or consequences of an issue, can significantly influence public understanding and attitudes50. Framing defines problems, diagnoses causes, makes moral judgments, and suggests remedies, thereby shaping how people process political information and form opinions on complex topics51.

Furthermore, Voter Behavior can be significantly influenced by personal emotional reactions to events entirely unrelated to public affairs, challenging traditional conceptions of citizen competence and democratic accountability48. The affect heuristic clearly demonstrates how emotions, rather than solely logic, sway individual choices12.

While emotional appeals can be manipulative and lead to poorly informed decisions10, understanding emotional contagion and framing effects through the CEF's lens allows for more ethical and effective communication. For instance, CEF's "Boosting" emotion can be used to inspire positive action and collective efficacy, rather than merely fear or anger7. Political communication can thus move beyond simplistic emotional manipulation to a more nuanced approach that leverages CEF's insights to connect authentically with the electorate6. This involves understanding how emotions like "Appreciating" can build positive reinforcement and "Boosting" can enhance self-belief, fostering a more engaged and resilient citizenry capable of critical evaluation.

4.4. Promoting Political Resilience and Well-being

The CEF emphasizes "Adaptive Emotional Cycling," a process where individuals actively utilize and transition between emotions to navigate life's ups and downs with greater efficacy7. This framework offers a robust mechanism for promoting resilience and well-being within the demanding political sphere.

The interplay of "Boosting" and "Accepting" is particularly important for resilience. "Boosting" provides the energizing motivation necessary to tackle challenging projects and overcome obstacles8, thereby enhancing endurance and building formidable resilience7. Simultaneously, "Accepting" allows for letting go of control, recognizing limitations, and embracing the need for rest and recovery7. This prevents burnout and promotes sustainable performance and long-term well-being7. This concept aligns closely with psychological acceptance, a core principle of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which focuses on accepting what is out of one's control to commit to valued actions7.

The mental health impact of political polarization is significant, contributing to widespread stress and sleep loss among citizens4. CEF's focus on "Accepting" and "Boosting" provides a framework for fostering individual and collective well-being within highly stressful political environments. This extends beyond mere individual coping mechanisms to suggest a systemic approach to political health. Recognizing and actively cultivating emotions like "Accepting" and "Boosting" can foster greater resilience among political actors, reducing the personal toll of public service and potentially leading to more stable and effective governance. Furthermore, promoting emotional well-being within the electorate can counteract the negative psychological effects of political strife, contributing to a healthier and more engaged citizenry.

5. Challenges and Limitations of an Emotion-Centric Approach in Politics

While the Core Emotion Framework offers a powerful lens for understanding and navigating political complexities, its application is not without challenges and limitations that warrant careful consideration.

5.1. Potential for Manipulation Through Emotional Appeals

The integral role of emotions in political decision-making and public opinion presents a significant ethical dilemma. While emotions are a natural part of human experience, an over-reliance on emotional appeals in policy debates can undermine the credibility of policymakers and advocates, lead to poorly informed decisions, and, critically, manipulate public opinion15. It is well-documented that politicians and media already exploit cognitive biases and emotional framing to sway public sentiment10. The CEF provides tools for intentional emotional activation7, and these tools, like any powerful instrument, could be used for either benevolent or manipulative purposes. The "marketplace of ideas," a foundational concept for democratic discourse, is particularly vulnerable to such emotional manipulation, potentially distorting rational debate10.

The Core Emotion Framework (CEF) posits that manipulation arises when certain dominant core emotions actively charge and control the others—preventing them from expressing themselves autonomously and redirecting them to serve the agenda of the more dominant emotions7. Each person has a unique emotional profile, with specific core emotions exerting greater influence over their psyche (as partially reflected in personality systems). These dominant emotions tend to suppress, block, or manipulate the others, effectively inhibiting their full expression7.

According to the CEF, when an individual consciously identifies and individuates each core emotion—whether through meditation, reflection, embodied action, or movement—it initiates a transformation of the entire emotional system. This shift moves the psyche from a maladaptive, controlling dynamic to one of adaptive emotional efficiency7.

In a healthy emotional ecosystem, each core emotion has space to breathe, contribute, and cycle. But in an emotional empire, one dominant emotion—say, fear or ambition—colonizes the others, redirecting their energy toward its own agenda. The CEF invites us to decolonize our emotional systems and restore adaptive cycling7.

This transformation cannot be verified or reliably contested until the mechanisms are fully understood—a process that demands deep reflection, experiential exploration and reasonable detanglement. In the mean` time, the CEF is supplying plenty of emotional intelligence that illuminates every step of the way.

The power of emotional influence in politics underscores an ethical imperative for emotional literacy. The application of CEF in politics necessitates a strong ethical framework. Education on emotional literacy should not only empower individuals to manage their own emotions effectively but also to critically discern and resist manipulative emotional appeals in political communication. This dual focus can foster a more robust, informed, and resilient public discourse, where emotional understanding serves to enhance rather than undermine democratic processes.

5.2. Complexity of Measuring and Applying Emotional Frameworks in Diverse Political Contexts

Applying a framework like the CEF across diverse cultural and political contexts presents significant challenges, particularly concerning measurement and interpretation. The field of emotional intelligence itself has faced criticism, with ongoing debates regarding the validity and reliability of its measurement instruments46. Translating these concepts to the nuanced and varied landscapes of global politics adds another layer of complexity. What constitutes "appropriate" emotional display, "rational" decision-making, or even the prioritization of certain emotions can vary significantly across different political cultures and societal norms.

While the CEF provides a universal framework for core emotions7, the expression, interpretation, and societal norms surrounding these emotions are deeply culturally mediated. For instance, the public display of "Accepting" (letting go) might be perceived differently in a collectivist society compared to an individualistic one. This necessitates that future research and practical application of CEF in politics be highly sensitive to cultural nuances, avoiding a one-size-fits-all approach. This requires the integration of qualitative research methods alongside quantitative ones to capture the rich complexity of emotional dynamics in varied political landscapes, ensuring that the framework is adapted and applied contextually.

5.3. Need for Empirical Validation of CEF's Specific Applications in Political Science

While the Core Emotion Framework draws on established psychological principles and neurobiological findings, its specific application and efficacy in resolving political questions require rigorous empirical confirmation7. The theoretical coherence of concepts like emotional cycling, for instance, needs further scientific investigation for full validation in real-world political settings7. Currently, much of the practical utility of CEF in political contexts is inferred from its alignment with existing research7. The leap from a psychological theory to demonstrable political impact requires dedicated, context-specific studies.

Future research should prioritize designing interventional studies that directly test the impact of CEF-based training on measurable political outcomes. This could include assessing improvements in negotiation skills among diplomats, observing reductions in political polarization within communities, or evaluating enhancements in public engagement and civic participation.

Utilizing advanced neuroimaging techniques could further illuminate the neural correlates of emotional processes during political decision-making, providing deeper mechanistic understanding14. Such rigorous empirical evidence is essential to solidify CEF's role as a valuable and validated tool in political science, bridging the gap between theoretical promise and practical application.

6. Conclusion: Towards an Emotionally Intelligent Polity

The Core Emotion Framework (CEF) offers a comprehensive, actionable, and neurobiologically-informed lens for understanding the complex interplay of cognition, emotion, and action in political behavior. By systematizing emotions into Head, Heart, and Gut categories, each with ten core processes, CEF moves beyond abstract emotional concepts to provide a practical vocabulary for emotional mastery in the political sphere. It serves as a crucial complement to traditional rational choice models, acknowledging the predictable deviations from pure rationality that are driven by inherent emotional and cognitive biases. This framework provides a more holistic and nuanced understanding of political phenomena, recognizing the human element at its core.

The implications of integrating CEF into political analysis are far-reaching, impacting leadership, policy-making, and citizen engagement. For political leadership, CEF can significantly enhance emotional intelligence, fostering greater self-awareness, improving self-regulation, cultivating empathy, and refining social skills7. This leads to more balanced and confident decision-making, increased resilience to the pervasive stresses of public service, and more effective approaches to conflict resolution7.

For policy-making, understanding how emotions influence risk perception, public acceptance, and the impact of communication framing15 allows policymakers to design interventions that resonate more authentically with human behavior6. This encourages the development of evidence-based policy that thoughtfully integrates emotional insights without resorting to manipulation. For citizen engagement, CEF can empower individuals to better understand their own emotional responses to political issues, critically evaluate emotionally charged political communications, and engage in more constructive discourse, thereby fostering resilience against polarization and misinformation4.

Looking ahead, future interdisciplinary research should focus on several key areas to further validate and expand the application of CEF in political science. Empirical validation of CEF's specific applications in political contexts is paramount, potentially utilizing neuroimaging techniques to observe the neural correlates of emotional processes during political decision-making14. Studies could explore the effectiveness of CEF-based interventions in fostering emotional intelligence among political actors, reducing polarization, and improving intergroup relations. Cross-cultural research is essential to understand how CEF's principles manifest and can be applied in diverse political systems, ensuring contextual sensitivity and avoiding a universalist bias. Finally, investigating the long-term impacts of cultivating specific CEF emotions on broader political outcomes, such as voter turnout, policy adoption, and the stability of democratic institutions, would be invaluable.

The comprehensive integration of CEF with political psychology, behavioral economics, and neuroeconomics points towards the emergence of a new sub-field: "Emotional Political Science." This emerging field would fundamentally re-conceptualize political behavior through an emotional lens, moving beyond merely adding emotion as a variable. It would prioritize the systematic study of emotional competencies in political actors, the intricate emotional dynamics of public opinion, and the deliberate design of emotionally intelligent policies and institutions. Such a development promises a more human-centered and ultimately more effective approach to understanding and navigating the inherent complexities of the political world, fostering a more emotionally intelligent polity.

Works cited

- Rational Actor Theory - The Decision Lab, accessed July 22, 2025, https://thedecisionlab.com/reference-guide/economics/rational-actor-theory

- Introduction to International Relations Lecture 3: The Rational Actor Model - Branislav L. Slantchev (UCSD), accessed July 22, 2025, http://slantchev.ucsd.edu/courses/ps12/03-rational-decision-making.pdf

- Behavioral economics, explained - University of Chicago News, accessed July 22, 2025, https://news.uchicago.edu/explainer/what-is-behavioral-economics

- The Psychology of Political Polarization - Psychiatrist.com, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.psychiatrist.com/news/the-psychology-of-political-polarization/

- (PDF) Decision-Making and Neuroeconomics - ResearchGate, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229544703_Decision-Making_and_Neuroeconomics

- Exploring Neuroeconomics and Dynamic Political Economy Trends Today, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/exploring-neuroeconomics-political-economy-trends

- Core Emotion Framework, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.coreemotionframework.com/

- The Core Emotion Framework (CEF) for Optimizing Capabilities, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.optimizeyourcapabilities.pro/

- Cognitive Biases in Politics - Number Analytics, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/cognitive-biases-in-politics

- Cognitive Campaign Biases, Political Decisions and Consequences - IISTE.org, accessed July 22, 2025, https://iiste.org/Journals/index.php/PPAR/article/download/61727/63709

- Prospect Theory and Political Decision Making - VU Research Portal, accessed July 22, 2025, https://research.vu.nl/files/2928151/261804.pdf

- Affect Heuristic - The Decision Lab, accessed July 22, 2025, https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/affect-heuristic

- Dual Process Theory: Embodied and Predictive; Symbolic and Classical - Frontiers, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.805386/full

- Dual Process Theory and the Political Belief Bias Effect - ResearchGate, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274372160_Dual_Process_Theory_and_the_Political_Belief_Bias_Effect

- The Power of Emotion in Shaping Public Policy - Number Analytics, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/emotion-in-public-policy

- Somatic marker hypothesis - Wikipedia, accessed July 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Somatic_marker_hypothesis

- What is Interoception? Understanding the Neuroscience Behind Self-Awareness, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.happyneuronpro.com/en/info/what-is-interoception/

- An insula hierarchical network architecture for active interoceptive inference - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9240682/

- The Insular Cortex: An Interface Between Sensation, Emotion and Cognition - ResearchGate, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380464465_The_Insular_Cortex_An_Interface_Between_Sensation_Emotion_and_Cognition

- Anterior Insular Cortex and Emotional Awareness - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3999437/

- Heuristics and Biases in Political Decision Making - Oxford Research Encyclopedias, accessed July 22, 2025, https://oxfordre.com/politics/oso/viewentry/10.1093$002facrefore$002f9780190228637.001.0001$002facrefore-9780190228637-e-974;jsessionid=3A332766487B7FDBE6852F211D7DAA06

- Executive dysfunction, brain aging, and political leadership | Politics and the Life Sciences, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-the-life-sciences/article/executive-dysfunction-brain-aging-and-political-leadership/00E5F00C476ADC5B9BE5E22AF306FCDF

- The role of prefrontal cortex in cognitive control and executive function - PubMed Central, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8617292/

- Neural Basis of the Development of Executive Function - J-Stage, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jjdp/30/4/30_202/_article/-char/en

- Brain Reward System - Simply Psychology, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.simplypsychology.org/brain-reward-system.html

- Neuroscience and addiction: Unraveling the brain's reward system | Penn LPS Online, accessed July 22, 2025, https://lpsonline.sas.upenn.edu/features/neuroscience-and-addiction-unraveling-brains-reward-system

- Brain Reward Pathways, accessed July 22, 2025, http://neuroscience.mssm.edu/nestler/nidappg/brain_reward_pathways.html

- Learning and motivation in the human striatum - ResearchGate, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51206439_Learning_and_motivation_in_the_human_striatum

- (PDF) The Neural Basis of Empathy - ResearchGate, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227707169_The_Neural_Basis_of_Empathy

- Decoding the neural basis of affective empathy: How the brain feels others' pain, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/03/250310134213.htm

- Emotional Intelligence and Conflict Management Style - UNF Digital Commons, accessed July 22, 2025, https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1415&context=etd

- Emotional Intelligence Conflict Resolution | Recognising, empathy - CPD Online College, accessed July 22, 2025, https://cpdonline.co.uk/knowledge-base/mental-health/emotional-intelligence-conflict-resolution/

- Emotion: An Evolutionary By-Product of the Neural Regulation of the Autonomic Nervous System - Sound Therapy International, accessed July 22, 2025, https://mysoundtherapy.com/wp-content/uploads/Emotion-an-evolutionary-approach-to-nerual-regulation-Porges.pdf

- What is Polyvagal Theory?, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.polyvagalinstitute.org/whatispolyvagaltheory

- Neural Mechanisms of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Chronic Pain: A Network-Based fMRI Approach - PubMed Central, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7892587/

- The Neurobiology of Activational Aspects of Motivation: Exertion of Effort, Effort-Based Decision Making, and the Role of Dopamine | Annual Reviews, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-psych-020223-012208?crawler=true

- How your brain works - Mayo Clinic, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/epilepsy/in-depth/brain/art-20546821

- Parietal Lobe - Physiopedia, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.physio-pedia.com/Parietal_Lobe

- GRATITUDE: A TOOL TO REDUCE STRESS, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.hhs.nd.gov/sites/www/files/documents/BH/Gratitude.pdf

- The Neuropsychology Of Gratitude | TheGratitudeJourney, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.thegratitudejourney.com/the-neuropsychology-of-gratitude

- The Neuroscience of Resilience: How to Bounce Back - YouTube, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O_05KlZSuvU

- Understanding resilience - Frontiers, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/behavioral-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00010/full

- Neurobiology of Resilience - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3580862/

- A Comprehensive Overview on Stress Neurobiology: Basic Concepts and Clinical Implications - Frontiers, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/behavioral-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00127/full

- The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Political Leadership: A Management Approach to Political Psychology - ResearchGate, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377838453_The_Role_of_Emotional_Intelligence_in_Political_Leadership_A_Management_Approach_to_Political_Psychology

- Full article: Study of emotional intelligence and leadership competencies in university students - Taylor & Francis Online, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2331186X.2024.2411826

- Facing Emotional Politicians: Do Emotional Displays of Politicians Evoke Mimicry and Emotional Contagion? | Request PDF - ResearchGate, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365492639_Facing_emotional_politicians_Do_emotional_displays_of_politicians_evoke_mimicry_and_emotional_contagion

- Personal Emotions and Political Decision Making: Implications for Voter Competence, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/working-papers/personal-emotions-political-decision-making-implications-voter

- Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1320040111

- Competitive Framing in Political Decision Making - Oxford Research Encyclopedias, accessed July 22, 2025, https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-964?p=emailAQF5HZvEdTypc&d=/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-964

-

Framing theory and political communication | Media and Politics Class Notes - Fiveable, accessed July 22, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/media-politics/unit-5/framing-theory-political-communication/study-guide/xqw2NLJHpbryePKh

-

Optimizeyourcapabilities.com. (2025). The Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Theoretical Synthesis Integrating Affective Neuroscience, Embodied Cognition, and Strategic Emotional Regulation for Optimized Functioning [Zenodo]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17477547

-

Optimizeyourcapabilities.com. (2025, November 14). A Proposal for Open Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Structural-Constructivist Model for Emotional Regulation and Psychological Flourishing. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SG3KM

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Compendium of Evidence-Based Psychotherapy Modalities: Reframed through the Core Emotion Framework (CEF). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17665533

- Bulgaria, J. (2025, November 21). Pre-Registration Protocol: Open Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF) Scale – Phase 1: Construct Definition, Item Generation, and Multi-Level Factor Structure Confirmation. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4RXUV

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). The Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Structural-Constructivist Model for Emotional Regulation and Adaptive Resilience in the Treatment of Anxiety. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17693163

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Extending the Core Emotion Framework: A Structural-Constructivist Model for Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17713676

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Structural Psychopathology of Major Depressive Disorder_ An Expert Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17713725