Reflections Beyond Glass: Mirroring Emotion with the Core Emotion Framework

While gazing into a mirror is a familiar human ritual, using an emotional mirror remains a unique challenge.

The Core Emotion Framework (CEF) offers a novel approach by crafting an emotional mirror through the lens of ten core emotions—Sensing, Calculating, Deciding, Expanding, Constricting, Achieving, Arranging, Appreciating, Boosting, and Accepting. This form of mirroring is simple, accessible, and cost-free, achievable by engaging with a visual representation—such as a banner or mural—that depicts these core emotional states.

This article explores the intriguing possibility that CEF's core emotions may recontextualize the controversial practice of handwriting analysis, commonly known as graphology.

Decoding Our Complexities: How the Core Emotion Framework (CEF) Offers Fresh Insight into Handwriting Analysis

What if the strokes we leave behind on paper—those loops, angles, and slants—aren’t just relics of motor control or personality quirks, but glimpses into an underlying emotional architecture?

The Core Emotion Framework (CEF) introduces a compelling possibility: that graphology, long dismissed by many as pseudoscience, may find new footing when reexamined through the lens of core emotional states. With its ten foundational emotions—Sensing, Calculating, Deciding, Expanding, Constricting, Achieving, Arranging, Appreciating, Boosting, and Accepting—the CEF provides a language for decoding not just behavior, but emotional intention.

In this article, we’ll investigate how visual prompts depicting these emotions can act as a mirror for internal states, and explore whether these emotional imprints correspond to stylistic signatures in handwriting. Could this synthesis reveal a deeper emotional logic behind the written form? Let’s find out.

An Examination of Letter Morphology and Psychoanalytic Concepts in Graphology

I. Introduction: Exploring the Link Between Handwriting and the Psyche

Graphology, defined as the analysis of handwriting to understand personality, boasts a history spanning over 2000 years, with more formal development emerging in the 17th century1. Its central premise posits that an individual's handwriting serves as a direct reflection of their personality, mental state, and emotional condition1. Proponents of graphology assert that a detailed examination of various characteristics, including letter size, slant, spacing between words and letters, and the shapes of letters, can yield profound insights into an individual's cognitive abilities, emotional states, and overall personality traits1.

The historical presence of graphology, from its ancient observations to its systematic, albeit unscientific, formalization in the 19th century, highlights a persistent human inclination to seek external, tangible manifestations of internal psychological states1. This historical trajectory reveals a societal curiosity that predates modern psychology and continues to influence popular perception, even in the face of scientific skepticism. The enduring nature of such theories underscores a fundamental human desire to decode the complexities of the self through observable phenomena.

This report investigates a specific proposed theory that establishes a direct correlation between distinct morphological components of letters—categorized as "head," "heart," and "legs"—and the foundational structural components of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theory: the Superego, Ego, and Id.

This theory further associates these letter parts and Freudian constructs with specific psychological traits. For instance, the "head parts" of letters (e.g., 'b', 't', 'l') are linked to the Superego, with connections to "sensing" and "perceiving." The "heart parts" (e.g., 'o', 'e', 'c') are associated with the Ego, reflecting traits such as "expanding" (natural slant, rounded shape), "achieving" (upright straight), and "constricting" (anti-natural slant, cornering). Finally, the "legs" of letters (e.g., 'j', 'g') are proposed to correspond to the Id, representing "instinctual aspects." This framework aligns with a broader graphological concept known as "handwriting zones."

This article aims to thoroughly research and present this proposed graphological theory. It will contextualize the theory within the established principles of both graphology and Freudian psychology. A critical examination will be conducted to assess the extent to which the specific claims of the theory are supported by existing literature, particularly concerning the proposed links between letter morphology and psychological traits. Furthermore, the article will evaluate the broader scientific validity and limitations of graphology as a diagnostic tool, providing an objective and evidence-based perspective.

II. Foundations of Personality: Freud's Id, Ego, and Superego

In Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theory, the Id represents the most primitive and inaccessible part of the personality, operating entirely within the unconscious mind3. It serves as the reservoir of uncoordinated instinctual needs, impulses, and desires, functioning solely on what Freud termed the "pleasure principle"3. This principle dictates that the Id seeks immediate gratification of all desires and urges, without any consideration for reality, logic, or moral constraints3. The Id is present from birth, forming the entirety of a newborn's personality, and is described as chaotic and unreasonable, possessing no inherent sense of right or wrong3. Its primary function is to reduce tension caused by unmet needs. Examples of its manifestations include fundamental biological drives such as hunger, thirst, and sexual urges, all demanding instant satisfaction4.

Developing from the Id during infancy, the Ego functions as the rational and realistic mediator within the psyche3. Its crucial role is to balance the impulsive demands of the Id, the moral dictates of the Superego, and the practical constraints imposed by external reality3. The Ego operates according to the "reality principle," which involves devising realistic and socially acceptable strategies to satisfy the Id's desires3. This often necessitates compromise or the postponement of gratification to avoid negative consequences from society3. The Ego functions across both conscious and unconscious levels of the mind, allowing it to interact with the external world while also managing internal impulses3. Freud famously illustrated the Ego's role by likening it to a rider attempting to harness and direct the superior energy of a horse, which represents the Id6. In this analogy, the rider (Ego) transforms the horse's (Id's) raw will into actionable plans, demonstrating its integrative and directive capacity6.

The Superego embodies the individual's moral conscience and internalized societal and parental standards, constantly striving for perfection and ideal behavior3. While operating predominantly unconsciously, its primary role is to ensure that the Ego manages the Id's demands in a morally acceptable manner4. This component of personality is classified into two parts: the "ego ideal" and the "conscience"4. The ego ideal gathers all morally acknowledged undertakings and rewards the Ego with feelings of pride and self-esteem when these are met4. Conversely, the conscience is responsible for disciplining morally wrong actions of the Ego through feelings of infamy, guilt, and humiliation4. The Superego actively criticizes and prohibits the expression of unacceptable drives, fantasies, feelings, and actions, working in direct contradiction to the Id's pursuit of instant self-gratification6.

A critical aspect of Freud's psychoanalytic theory is the dynamic and often conflicting interplay among the Id, Ego, and Superego. A healthy personality, according to Freud, is characterized by an effective Ego that successfully mediates and balances the demands from the impulsive Id, the moralistic Superego, and the practicalities of external reality3. Any significant imbalance within this system, where one component dominates excessively, is theorized to contribute to various forms of mental illness or maladaptive behaviors3. This suggests that for any proposed graphological correlation to be truly comprehensive, it would ideally reflect not just isolated personality traits but also the proportionality and dynamic equilibrium between these psychic structures. The theoretical framework implies that a balanced personality is one where these forces are integrated effectively, rather than one being overly suppressed or expressed.

III. The Graphological Framework: Handwriting Zones and Psychoanalytic Correspondence

In graphology, handwriting is systematically divided into three distinct "zones": the Upper Zone, the Middle Zone, and the Lower Zone7. This zonal theory is attributed to the Swiss psychoanalyst Max Pulver, who observed these divisions as a fundamental aspect of handwriting analysis8. The "baseline" of writing, whether actual or hypothetical, is considered by graphologists to represent the "line of consciousness," with any strokes extending below it delving into the realm of the unconscious8.

These zones are associated with different aspects of personality:

- Upper Zone (Sphere of Imagination/Intellect): This zone, which graphologists associate with the Superego, encompasses the extended upward strokes, known as ascenders, of letters such as 'b', 'd', 'h', 'k', 'l', and 't'7. It is believed to represent a person's imaginative abilities, intellectual pursuits, and abstract thinking. Graphologically, it is associated with concepts like abstraction, creativity, ethical beliefs, fantasy, philosophy, politics, religious aspirations, idealism, scientific thought, speculation, and illusions7. This zone also correlates with future aspirations7.

-

Middle Zone (Sphere of Actuality): This zone, associated with the Ego, comprises the main body of letters that do not extend above or below the baseline, such as 'a', 'c', 'e', 'm', 'n', 'o', 'r', 's', 'u', 'v', 'w', and 'x'7. It reflects how an individual navigates daily life, interacts socially, and handles practical matters. It is linked to adaptability to daily life, rational behavior, self-assurance, and sociability, as well as the intensity of focus on day-to-day requirements7. The middle zone is also associated with the present moment7.

- Lower Zone (Sphere of the Unconscious/Instincts): This zone, directly linked to the Id, includes the descending strokes, or descenders, of letters like 'f', 'g', 'j', 'p', 'q', and 'y'7. It is interpreted as representing subconscious drives, emotional depth, and fundamental physical instincts. Associations include basic biological desires, inclination towards sex and romance, interest in sports and adventure, and fundamental drives for money, health, and physical well-being7. This zone is also connected to past influences7.

Beyond simply identifying the zones, graphological theory posits an "ideal" proportion for these handwriting zones in a "healthy adult." This ideal suggests that the middle zone should be approximately half the size of the upper and lower zones, with the upper and lower zones being roughly equal in length (e.g., a 1:0.5:1 or 2:1:2 ratio, depending on the model)7. Any significant deviation from this proportionality is interpreted as an imbalance in personality, indicating a dominant focus—whether intellectual, social, or instinctual—that may lead to certain psychological inclinations or challenges7. This introduces a quantitative, albeit unvalidated, dimension to the qualitative interpretations. The concept implies that the relative emphasis a writer places on these zones reflects the balance of their psychic energy, with disproportionate zones suggesting areas of overemphasis or underdevelopment in their personality.

IV. Deconstructing the Letter: Specific Parts and Proposed Psychological Links

A. Head Parts (Upper Zone): "b", "t", "l" and the Superego

Ascenders are the portions of lowercase letters that extend above the meanline (or x-height), forming the "head parts" of letters such as 'b', 't', and 'l'10. Within graphological theory, these ascenders are associated with the upper zone, which represents the Superego7. This zone is interpreted as reflecting an individual's intellectual pursuits, abstract thinking, idealism, and ethical beliefs7.

Specific interpretations related to these letters include: long ascenders, particularly in 'h', which can signify philosophical imagination13. The formation of the crossbar on the letter 't', a key feature in the upper zone, is linked to self-esteem and ambition. A high crossbar on 't' indicates high self-esteem, ambition, and the ability to plan ahead, suggesting high goals and personal expectations13. Conversely, a t-bar crossed very low suggests low self-esteem and a fear of failure13. A t-bar positioned above the stem may indicate setting goals higher than can be realistically accomplished14. For the letter 'l', narrow loops suggest tension caused by self-limitation or restriction, while wide 'L' loops are interpreted as indicative of an unstructured, easygoing, and relaxed disposition15.

Available research confirms that the letters ‘b’, ‘t’, and ‘l’ are typically found in the upper zone of handwriting. This zone is consistently linked to the Superego, representing idealism, abstract reasoning, and intellectual aspiration7. Within the context of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF), a highly developed or vertically emphasized upper zone appears to resonate with the core emotion of Sensing.

In CEF terms, Sensing reflects a kind of emotional yearning—an attunement to the unseen, the undefined, and the supernatural. It is the drive to perceive subtle data, to reach beyond immediate sensory input and grasp patterns that lie just outside rational cognition. When mapped onto handwriting, this emotional orientation could manifest through a visually pronounced upper zone: elongated ascenders, lifted loops, and airy spacing.

This parallel invites a provocative hypothesis: that emotional posture—particularly Sensing—may leave symbolic imprints not just in movement and decision-making, but in the very form of written expression.

B. Heart Parts (Middle Zone): "o", "e", "c" and the Ego

The middle zone, representing the "heart parts" of letters, comprises the main body of letters such as 'a', 'e', 'o', 'm', 'n', 'r', and 's' that do not extend above or below the baseline7. This zone is consistently associated with the Ego7 and reflects an individual's engagement with daily reality, social interactions, and practical matters7. It is linked to rational behavior, self-assurance, and adaptability to everyday life7. The size of capital letters, which often reside within or influence the middle zone, can also indicate ego strength, with larger capitals suggesting an inflated sense of self-importance.13

An analysis of 'o', 'e', and 'c' in relation to the proposed traits of "expanding," "achieving," and "constricting" reveals several connections within graphological interpretations:

- Letters "o" and "e": These are quintessential middle zone letters7. Rounded letters, including 'o' and 'e', are generally associated with imagination, creativity, and artistry15. Studies suggest that round letters evoke more pleasant feelings for readers and contribute to faster reading speeds16. Organic shapes are perceived as fluid, harmonious, warm, and authentic (-expanding fused with sensing and achieving)17. Conversely, overly round writing may indicate immaturity and dependency (-expanding fused with accepting and boosting)18. Specific to loops in these letters, narrow 'e' loops can indicate skepticism or suspicion, suggesting a guarded and stoic nature (-constricting fused with arranging)15. Circles within 'o's, especially if large and crossing, can signify secretiveness or even pathological lying, indicating untrustworthiness (-excessive calculating)13.

- Letter "c": Also a middle zone letter. Pointed or angular letters, such as a sharp 'c', are linked to intensity, aggression, and intelligence15. Angular handwriting generally indicates aggressiveness, directness, and high energy (-constricting + boosting)14. Extreme squaring of letters, which could apply to a very cornered 'c', might even suggest psychosis in some graphological interpretations18.

The concept of "expanding," associated with a natural slant and rounded shape, aligns strongly with graphological interpretations of a rightward slant. This slant indicates open-mindedness15, high emotional expressiveness14, and a "heart-ruled," impulsive person with a constant need for affection13. The "roundy shape" aspect is supported by the associations of rounded letters with creativity, pleasantness, and natural fluidity15.

"Achieving," linked to an upright straight style, corresponds well with a vertical or no slant. This suggests rationality, level-headedness15, emotional control, a strong work ethic, and steadfast, reliable energy (-achieving fused with boosting)14. These traits are generally considered conducive to achievement and practical effectiveness.

"Constricting," associated with an anti-natural slant and cornering, aligns with a leftward slant. This indicates shyness, reserve, emotional withdrawal14, and guardedness15. The "cornering" aspect is supported by interpretations of pointed or angular letters, which suggest skepticism, intensity, aggression, or a more guarded and stoic nature14.

The proposed associations for "heart parts" ('o', 'e', 'c') and their psychological concepts ("expanding," "achieving," and "constricting") show a significant general alignment with established graphological interpretations of letter shape (rounded vs. angular) and slant (right, vertical, left)13. This shows a correlation (or "overlap") between the CEF and fundamental graphological principles.

C. Legs (Lower Zone): "j", "g" and the Id

Descenders are the portions of lowercase letters that extend below the baseline, forming the "legs" of letters such as 'j' and 'g'10. Graphologically, these descenders are associated with the lower zone, which is directly linked to the Id7. The letters 'j' and 'g' are explicitly identified as letters with prominent descenders, placing them firmly within the lower zone7. The lower zone, in turn, is consistently associated with the Id and a range of "instinctual aspects"7. These include "basic biological drives and desires," "inclination towards sex and romance," "interest in sports and adventure," and "basic drives for money, health, and sex"7. These interpretations align directly with the CEF compartmant of the Gut.

Furthermore, the available literature provides detailed interpretations for the formation of these descenders, which elaborate on how these instinctual aspects might manifest. For instance, large and wide lower loops in 'y', 'g', and 'j' are said to reveal strong physical imagination and gullibility13. Long, narrow loops in 'y' or 'g' can indicate social selectivity, suggesting carefulness in choosing close relationships13. Retraced lower loops in 'y', 'g', and 'j' suggest a lack of trust or fear of intimacy, indicating an anti-social tendency13. Downward hooks on 'g's and 'y's might signify a fear of success19. Incomplete lower loops can indicate physical frustration in areas such as relationships, exercise, or sexual activity13. More extreme or distorted loops (e.g., exaggerated, stunted, reversed, broken) are even cited as "danger signs" in psychopathic analysis, linked to impaired emotional expression, inhibition, warped emotional responses, or rebelliousness18.

The proposed link between "legs" ('j', 'g'), the lower zone, and the Id's "instinctual aspects" is strongly and consistently supported by the graphological literature. The literature further enriches the broad "instinctual aspects" by detailing how these fundamental drives might be expressed, channeled, or inhibited in an individual's personality, demonstrating a consistent thematic connection within graphological theory. The specific morphological variations of these descenders offer nuanced interpretations of an individual's relationship with their primal urges and physical realities.

V. Critical Evaluation: Scientific Standing and Limitations of Graphology

Discussion of graphology's classification as a pseudoscience.

Despite its long history and popular appeal, graphology is overwhelmingly classified as a pseudoscience by the mainstream scientific community1. This designation stems from the consistent failure of most empirical studies to substantiate the validity and reliability of its claims regarding personality assessment14. Historically, graphology has been associated with other discredited "sciences" such as phrenology and eugenics, which similarly relied on "fake empiricism" to make discriminatory claims about individuals21. The historical grouping of graphology with these other pseudosciences reveals a pattern of attempting to derive complex psychological or social conclusions from superficial physical traits, often leading to problematic and discriminatory applications. Understanding this historical lineage is essential for comprehending the broader societal implications and the inherent dangers of accepting such claims without rigorous scientific validation.

Review of empirical studies on graphology's validity and reliability in assessing personality traits.

A significant body of empirical research has scrutinized graphology's claims, with findings consistently demonstrating "little or no validity"14 and concluding that it is "useless at best" for interpreting handwriting analysis14. Correlational studies, which examine the relationship between handwriting features and validated personality questionnaire results (e.g., NEO-FFI, EPQ-R), have largely yielded ambiguous or negative outcomes23. For instance, studies have found few statistically significant correlations between handwriting parameters and traits like psychoticism or extraversion23.

A fundamental flaw highlighted by empirical studies is graphology's demonstrable lack of discriminatory power23. A notable finding is that general features like a "medium size of letters" or "medium pressure" were found to correlate with

all major personality traits, including neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness23. This renders such analyses meaningless for providing specific, individualized personality assessments, as they cannot differentiate between distinct personality characteristics. This undermines the core premise of graphology as a tool for profiling distinct personality characteristics, indicating a critical methodological weakness rather than simply an absence of evidence. While some research indicates correlations between handwriting and demographic factors like gender22 or observable changes due to neurological conditions14, these findings are distinct from and do not validate graphology's claims of assessing deep-seated personality traits or Freudian constructs. Such observations fall within the realm of medical or forensic analysis, not personality profiling.

Distinction between graphology and forensic handwriting analysis or typographic studies.

It is critical to differentiate graphology, which purports to diagnose psychological traits, from legitimate fields such as forensic handwriting analysis24. Forensic analysis is a scientific discipline focused on authenticating the authorship of a document, comparing handwriting samples for identification purposes, rather than inferring personality21. Its methodology relies on observable, measurable characteristics for comparative analysis, not subjective psychological interpretation.

Similarly, typographic studies and linguistics examine letterforms and their arrangement for legibility, readability, and aesthetic impact16. For example, research shows that round letter shapes can evoke more pleasant feelings and facilitate faster reading speeds16, and that overall word shape influences readability26.

These fields operate on entirely different scientific principles and objectives compared to graphology's psychological claims. Graphology often attempts to bolster its perceived credibility by conflating itself with these legitimate scientific or artistic disciplines that also deal with handwriting or letterforms16. This creates a misleading impression that graphology shares the same scientific rigor, but the fundamental methodologies, objectives, and empirical bases of these fields are distinct. This distinction is vital for understanding the boundaries of scientific inquiry and to avoid being misled by superficial similarities.

Consideration of alternative factors influencing handwriting (e.g., motor skills, neurological conditions).

Handwriting is a complex motor skill influenced by a multitude of factors beyond stable personality traits. These include biomechanical elements such as muscle stiffness and elasticity2, age-related changes, failing eyesight, and neurological conditions like ataxia24. Educational background and personal habits also significantly shape an individual's penmanship27. Furthermore, transient emotional states can temporarily alter handwriting characteristics, such as pressure or regularity of strokes2. For instance, someone experiencing anger might exhibit heavier pressure and more irregular strokes compared to when calm20.

Recent research highlights that the act of writing by hand leads to more elaborate brain connectivity patterns compared to typing, suggesting its importance for learning and memory formation28. This underscores that handwriting is a sophisticated neuro-motor and cognitive process, rather than a simple, direct, and unadulterated expression of deep-seated personality or Freudian structures. The pervasive influence of numerous non-psychological factors on handwriting (biomechanical, neurological, educational, transient emotional states, and even the act of writing itself impacting brain activity) introduces significant confounding variables2. This makes it scientifically unsound to isolate specific handwriting features and attribute them solely to stable personality traits or Freudian constructs, as graphology attempts to do. The observed variations in handwriting are likely multi-factorial, rendering simplistic, singular psychological interpretations unreliable.

VI. Conclusion: Synthesis and Future Perspectives

The link between specific parts of letters (head, heart, legs) to Freudian psychological concepts (Superego, Ego, Id) and associated traits, demonstrates a clear conceptual alignment with the established graphological model of handwriting zones (upper, middle, lower). The general associations—where the upper zone/head parts relate to intellect and idealism (Superego), the middle zone/heart parts to daily reality and social interaction (Ego), and the lower zone/legs to instincts and subconscious drives (Id)—are consistently reflected in the graphological literature.7 Furthermore, the specific proposed traits for the "heart parts" (expanding, achieving, constricting) find general parallels in graphological interpretations of slant and letter shape13, and the "instinctual aspects" of the "legs" are richly detailed by interpretations of lower loops13. This consistency within graphological theory suggests a coherent internal logic for the proposed model.

Despite the internal consistency and intuitive appeal of certain graphological theories, including the zonal model and the specific associations explored, the overwhelming scientific consensus firmly classifies graphology as a pseudoscience1. Rigorous empirical studies have consistently failed to provide robust evidence for its claims in personality assessment, demonstrating little to no significant or reliable correlation between handwriting features and validated personality traits14. The presence of numerous confounding variables—such as biomechanical factors, neurological conditions, age, education, and transient emotional states—further undermines graphology's diagnostic utility and its ability to accurately reflect deep-seated psychological structures2. The inability of graphological features to discriminate between different personality traits, as evidenced by features correlating with multiple or all traits, fundamentally weakens its scientific standing23.

The enduring appeal of theories like the one presented in this inquiry likely stems from a deep-seated human desire to find hidden meanings and direct, observable links between outward behaviors and complex internal psychological states. The intuitive mapping of "head" to intellect, "heart" to emotion, and "legs" to instincts creates a compelling, easily digestible narrative that offers a perceived shortcut to understanding personality.

This persistence and internal coherence of graphological theories, despite a profound lack of empirical support, highlight a fundamental aspect of human cognition: the powerful tendency to find patterns and construct coherent narratives, even in the absence of genuine causal links21. This phenomenon underscores the critical distinction between anecdotal observation or theoretical speculation and the demands of rigorous scientific validation. The intuitive mapping offered by such theories provides a sense of understanding and control, which can be highly appealing, but true scientific inquiry necessitates a more disciplined and evidence-driven approach. For a comprehensive and reliable understanding of human psychology, reliance on theories supported by robust, replicable empirical evidence remains paramount.

It is suggested, however, that the Core Emotion Framework (CEF), through its precise articulation of core emotional states, may meaningfully challenge the persistent negative findings against graphology. This reconsideration is grounded in three key dimensions:

A. Measurement

For any theory to be rigorously validated—or invalidated—through reproducible research, it must first offer a coherent conceptual structure that allows for measurable differentiation. Personality is composed of a spectrum of emotional contradictions that are universal, yet expressed through varying degrees and combinations. What is lacking in graphology is a consistent emotional baseline.

The CEF is the first framework to offer such granular emotional clarity, enabling a structured and quantifiable approach. Each core emotion within the CEF can be assigned a scalar value from 0 to 10, with emotional fusions tracked across dominant expressions within an analyzed script. This systematization allows for empirical emotional profiling, which could bring reproducible validity to emotional interpretations rooted in handwriting.

B. Conceptualization

Graphologists often interpret behavioral tendencies, but these interpretations are prone to projection—attributing actions to a writer that may not align with their choices or internal moral compass. For example, one person may feel entirely justified while engaging in theft, whereas another may experience guilt simply for withholding personal information. These contrasts cannot be understood without mapping the writer’s emotional architecture.

By applying the CEF’s emotional map, a graphologist could assess the emotional posture rather than predict behavior. Instead of saying “this person is deceptive,” the analyst might describe a fusion of Calculating, Constricting, and Accepting, which could signal tension between strategic thinking and relational vulnerability. This reframing keeps analysis rooted in emotional balance, not speculative judgment.

C. Fundamentality

One of the fundamental critiques that led to graphology’s fall from academic grace is its tendency to overextend—claiming causal relationships between graphic traits and fixed behavioral outcomes. To revive its credibility, graphological interpretation must remain consistent with core emotional structures, avoiding over-theoretical detours and speculative extrapolations.

By anchoring interpretation in the CEF’s structured emotional model, graphology could transform from a predictive system into a descriptive tool for emotional insight, echoing the evolving emphasis on emotional intelligence in behavioral sciences.

VII. The Human Drive for Understanding: Mirroring, the Core Emotion Framework, and the Enduring Appeal of Graphology

Humans possess an innate drive to understand and connect with others, a process often facilitated by "mirroring"—the unconscious mimicry of behaviors and body language to establish rapport and build connection during social interactions. This fundamental desire extends to seeking insights into another person's personality and internal states. Graphology, despite its classification as a pseudoscience, taps into this deep-seated human need by offering a seemingly accessible method to "read" an individual's character directly from their handwriting. People often associate specific handwriting styles with traits like confidence, creativity, or organization, fulfilling a perceived need for understanding.28

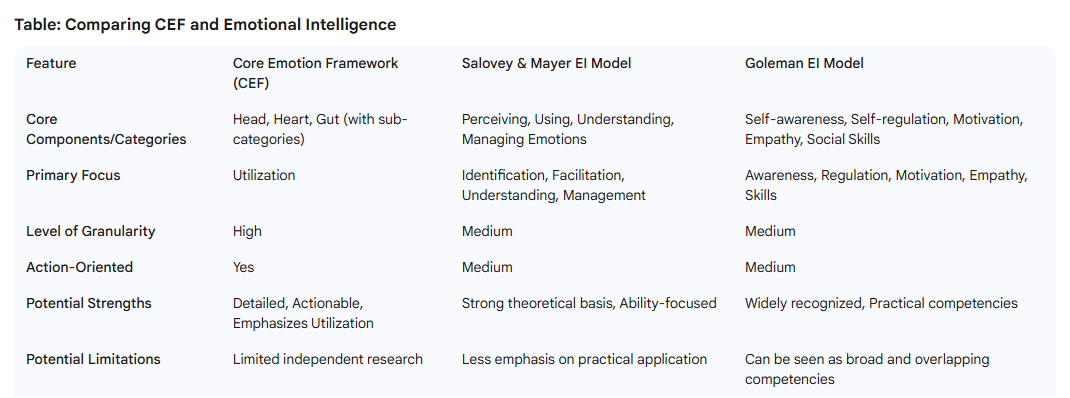

However, a more scientifically robust approach to understanding the fundamental building blocks of human emotions and reactions is provided by the Core Emotion Framework (CEF). The CEF identifies 10 fundamental mental operations—such as Sensing, Calculating, Deciding, Expanding, Constricting, Achieving, Arranging, Appreciating, Boosting, and Accepting—that serve as the "building blocks" of all human emotions and reactions. Mastering these powers can lead to profound emotional agility and personal growth, allowing for a deeper understanding of one's own emotional machinery. While CEF primarily focuses on self-understanding, a refined awareness of one's own emotional processes can enhance the ability to interpret and relate to the emotional states of others, providing a more robust foundation for "personality mirroring" than graphology's unproven claims1. Unlike graphology, which has consistently failed to demonstrate validity in personality assessment1, CEF is rooted in understanding the biological and cognitive mechanisms of emotion.

The Core Emotion Framework can also shed light on the enduring appeal of graphology itself. While graphology lacks scientific merit for personality diagnosis, the human brain's natural inclination to find patterns and interpret cues—even in complex motor skills like handwriting—can lead individuals to perceive personality traits, thereby satisfying a desire for understanding28. CEF highlights the intricate cognitive processes involved in interpreting internal and external cues, which, in the context of graphology, may result in subjective interpretations rather than objective insights. This perspective helps explain the persistence of graphological beliefs: they fulfill a powerful human need to seek meaning and connection, even through unscientific means, by attempting to "mirror" another's internal state from external manifestations. Thus, while graphology may not offer true psychological insight, its popularity underscores the profound human drive for understanding, a drive that is more reliably addressed through scientifically supported frameworks like the Core Emotion Framework.

Works cited

- Graphology: Understanding Handwriting to Analyze Personalities, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.psychologs.com/art-of-graphology-understanding-handwriting-to-analyze-personalities/

- Handwriting Analysis | PDF | Graphology | Behavioural Sciences - Scribd, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/102241055/82779161-Handwriting-Analysis

- Id, Ego, and Superego - Simply Psychology, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.simplypsychology.org/psyche.html

- Id Ego And Superego Analysis - 1790 Words - Cram, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.cram.com/essay/Id-Ego-And-Superego-Analysis/PK4ECC5KUZKW

-

MS in Psychology Insight: Id, Ego, And Superego - Walden University, accessed July 21, 2025,

- Id, ego and superego - Wikipedia, accessed July 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Id,_ego_and_superego

- Zones in Handwriting - Heyzine, accessed July 21, 2025, https://cdnc.heyzine.com/files/uploaded/5ec716dd8d7e87f5245a51d35d57b300674d190e-1.pdf

- Graphology zones define your personality - YouTube, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/shorts/0NwlYKnw95U

- Freud & Jung – Written Revelations - Personality Type in Depth, accessed July 21, 2025, https://typeindepth.org/freud-jung-written-revelations/

- Type Terminology - UCDA, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.ucda.com/type-terminology-part-3/

- Ascender (typography) - Wikipedia, accessed July 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ascender_(typography)

- Typography: Anatomy of a Letterform - Designmodo, accessed July 21, 2025, https://designmodo.com/letterform/

- Handwriting Analysis Quick Reference Guide for Beginners, accessed July 21, 2025, https://mrskubacki.weebly.com/uploads/8/7/3/0/87301008/handwriting_quick_reference_guide.pdf

- Science and History of Handwriting Analysis - Edinformatics, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.edinformatics.com/forensic/handwriting_analysis.htm

- Handwriting Analysis: What It Says About Your Personality - wikiHow, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.wikihow.com/Tell-What-Someone-is-Like-from-Their-Handwriting

- Influence of letter shape on readers' emotional experience, reading fluency, and text comprehension and memorisation - Frontiers, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1107839/full

- Psychology of Shapes in Design: A Guide for Visual Storytelling - DocHipo, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.dochipo.com/psychology-of-shapes/

- Handwriting analysis: A psychopathic viewpoint - IJIP, accessed July 21, 2025, https://ijip.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/18.01.108.20210901.pdf

- Your handwriting: What can it reveal about you? - University Times, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.utimes.pitt.edu/archives/?p=8753

- Psychology of Handwriting: What Does Your Penmanship Say About You?, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.printedpens.com.au/blog/psychology-of-handwriting-what-does-your-penmanship-say-about-you.htm

- Sorry, Graphology Isn't a Real Science - JSTOR Daily, accessed July 21, 2025, https://daily.jstor.org/graphology-isnt-real-science/

- The write stuff: Evaluations of graphology, the study of handwriting analysis - ResearchGate, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232555922_The_write_stuff_Evaluations_of_graphology_the_study_of_handwriting_analysis

- Lack of evidence for the assessment of personality traits using handwriting analysis, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271383069_Lack_of_evidence_for_the_assessment_of_personality_traits_using_handwriting_analysis

- Graphology and the psychology of handwriting, accessed July 21, 2025, https://archive.org/download/graphologypsycho00downuoft/graphologypsycho00downuoft.pdf

- Letterform - Wikipedia, accessed July 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Letterform

- Typography - Wikipedia, accessed July 21, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Typography

- the influence of personal handwriting styles on first impressions and - RESEARCH ARTICLE INTRODUCTION, accessed July 21, 2025, https://ijramr.com/sites/default/files/issues-pdf/5809.pdf

- Handwriting but not typewriting leads to widespread brain connectivity: a high-density EEG study with implications for the classroom - Frontiers, accessed July 21, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1219945/full

-

Optimizeyourcapabilities.com. (2025). The Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Theoretical Synthesis Integrating Affective Neuroscience, Embodied Cognition, and Strategic Emotional Regulation for Optimized Functioning [Zenodo]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17477547

-

Optimizeyourcapabilities.com. (2025, November 14). A Proposal for Open Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Structural-Constructivist Model for Emotional Regulation and Psychological Flourishing. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SG3KM

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Compendium of Evidence-Based Psychotherapy Modalities: Reframed through the Core Emotion Framework (CEF). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17665533

- Bulgaria, J. (2025, November 21). Pre-Registration Protocol: Open Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF) Scale – Phase 1: Construct Definition, Item Generation, and Multi-Level Factor Structure Confirmation. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4RXUV

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). The Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Structural-Constructivist Model for Emotional Regulation and Adaptive Resilience in the Treatment of Anxiety. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17693163

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Extending the Core Emotion Framework: A Structural-Constructivist Model for Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17713676

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Structural Psychopathology of Major Depressive Disorder_ An Expert Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17713725