The Embodied Voice: How Emotion and Neurobiology Shape Communication and Influence

The human voice is a powerful conduit for emotion, but how can we consciously build and leverage this connection? This article presents an interdisciplinary analysis, demonstrating how the Core Emotion Framework's (CEF) ten core emotions map to specific brain functions that underpin vocal communication. Uncover practical insights for speakers, performers, and leaders to achieve greater vocal resilience, emotional resonance, and influence.

Unlocking Vocal Potential: A Neuro-Emotional Approach to Voice Building and Persuasion

Why do some voices captivate while others fall flat?

This article reveals the neurobiological and emotional secrets behind effective vocal communication. By integrating the Core Emotion Framework (CEF) with behavioral science, we show how understanding and managing emotions like "Constricting" for calm or "Boosting" for confidence directly impacts vocal quality and persuasive ability. Read on to discover how to build a voice that truly resonates.

The Science of Sound and Sentiment: Integrating Core Emotions for Impactful Vocal Expression

I. Executive Summary

Vocal communication stands as a fundamental pillar of human interaction, serving as a powerful conduit for expressing and perceiving emotions, thereby shaping social dynamics and influence. This report delves into the intricate neurobiological mechanisms that govern vocal production and perception, highlighting key brain regions such as the insula cortex, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and the pervasive dopaminergic pathways. It examines how various theoretical frameworks of emotion, including the Core Emotion Framework, basic emotion theories, and dimensional models, contribute to understanding the vocal manifestation of affective states.

Furthermore, the report explores the multimodal nature of emotional communication, emphasizing the critical role of prosody and acoustic features. Through case studies in political communication, consumer behavior, and therapeutic applications, the profound impact of vocal cues on persuasion and well-being is illuminated. Finally, the ethical considerations inherent in leveraging neurobiological insights for influence are addressed, alongside a discussion of emerging research trends and future directions in this interdisciplinary field.

II. Introduction: The Voice as a Nexus of Neurobiology, Emotion, and Influence

Vocal communication is an omnipresent and indispensable aspect of human interaction, acting as a primary channel for social and emotional exchange throughout an individual's life. From the earliest stages of development, where infants respond instinctively to the affect-laden vocal expressions of their caregivers, to the complex exchanges of adulthood, vocal communication often holds a prevalence in daily life comparable to, or even exceeding, facial expressions1. The human voice is recognized as a potent social signal, capable of conveying a speaker's identity and emotional state even when visual cues are absent2.

The pervasive and fundamental role of vocal communication across the lifespan, exemplified by its early developmental importance in mother-infant interactions and its continued relevance in modern communication modalities like phone calls, underscores an evolutionary prioritization of vocal cues for social bonding and information transfer. This suggests that the brain's processing architecture for vocal emotion is deeply ingrained and highly efficient, potentially even prioritized over other sensory inputs in certain contexts. Such a deeply rooted biological significance implies that vocal communication is not merely a learned skill but an evolved capacity crucial for human sociality and survival.

This report systematically explores how the brain orchestrates both the production and perception of vocalizations, how emotions are intricately encoded within and decoded from vocal cues, and how these complex neurobiological and emotional processes collectively contribute to the capacity for influence and persuasion across diverse human domains. The discussion integrates cutting-edge insights from affective neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and communication studies to provide a comprehensive understanding of this multifaceted phenomenon.

III. Neurobiological Architecture of Vocalization and Emotion

The human voice, a primary tool for communication, is intricately controlled and interpreted by a complex network of brain regions. Understanding this neurobiological architecture is crucial to appreciating how emotions are embedded in and extracted from vocalizations, ultimately shaping their influential power.

Brain Regions Governing Vocal Production and Perception

- The Insula Cortex: Interoception, Emotional Awareness, and Vocal Cues

The insula cortex plays a critical and multifaceted role in translating bodily signals, a process known as interoception, which forms a fundamental basis for emotional awareness3. Functionally, the insula acts as a central hub, integrating emotional, cognitive, and sensory-motor systems. It is instrumental in various processes including social cognition, empathy, reward-driven decision-making, arousal regulation, reactivity to emotional stimuli, and the subjective perception of emotions3. Specifically, the anterior insula is linked to the subjective experience of emotions, while the posterior insula is involved in receiving and interpreting sensorimotor sensations3. Research also indicates a specific role for the right insula in the discrimination of durations, although its direct involvement in emotion-related temporal distortion remains distinct4.

The insula's pivotal role as an integrator of interoceptive and emotional signals suggests a direct and profound link between an individual's internal physiological state and their vocal expression of emotion.

This implies that authentic emotional vocalizations are not merely learned or consciously controlled behaviors but are deeply rooted in real-time bodily feedback. When an individual experiences an emotion, associated physiological changes—such as alterations in heart rate, muscle tension, or breathing patterns—are detected and processed by the insula. These internal sensations then influence the vocal apparatus, leading to observable changes in vocal cues like pitch, volume, rhythm, and tone.

Consequently, genuine emotional vocalizations are inherently powerful and difficult to consciously fake entirely, as they are a direct manifestation of underlying physiological states. This also suggests that cultivating interoceptive awareness, for instance through mindfulness practices, which have been shown to alter insular activation3, could potentially enhance the authenticity and impact of emotional expression through voice. By becoming more attuned to their internal bodily signals, individuals might gain finer control over the nuanced physiological underpinnings of their vocal delivery, leading to more authentic and compelling emotional communication.

- The Prefrontal Cortex: Emotional Regulation, Decision-Making, and Vocal Control

The prefrontal cortex (PFC), particularly the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), is a critical area for processing social stimuli, including both facial expressions and vocalizations, which are fundamental for effective communication5. Beyond social processing, the PFC is deeply involved in higher-order cognitive functions such as decision-making under uncertainty and the evaluation of consequences6. Furthermore, dysfunction in the prefrontal cortex, alongside the amygdala, has been linked to impaired emotion regulation, particularly in individuals exhibiting psychopathic traits7. The inferior frontal cortex, a part of the PFC, is specifically implicated in the evaluation of prosody and the emotional content conveyed through voices8. The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) plays a key role in self-referential processing, empathy, and theory of mind, all essential components of social cognition9.

The PFC's integrated involvement in emotional regulation, vocal processing, social cognition, and decision-making suggests that effective vocal influence relies heavily on the speaker's sophisticated ability to not only regulate their own emotional expression but also to accurately infer and adapt to the emotional states and cognitive processes of their audience. This highlights a crucial top-down, cognitive control mechanism over emotional vocal expression and perception, distinguishing it from more automatic, subcortical responses and enabling strategic, adaptive communication.

For a speaker to exert influence, they must consciously choose how to modulate their voice, a process deeply rooted in the PFC's role in decision-making and evaluating consequences. Simultaneously, the mPFC's involvement in empathy and theory of mind allows the speaker to infer the listener's emotional state and cognitive processing, enabling real-time adjustments to their vocal delivery for maximum impact. This sophisticated integration underscores that vocal influence is not merely an emotional outburst but often a calculated, cognitively-mediated process, reflecting the brain's capacity for deliberate control over affective communication.

- The Amygdala: Processing Emotional Salience in Vocal Stimuli

The amygdala is a critical brain region involved in emotion regulation, with reduced activity in this area linked to psychopathic traits7. More broadly, it plays a pivotal role in processing emotional information, particularly those related to fear and anxiety9. Its primary function includes detecting emotionally salient stimuli, such as fearful or threatening faces, and rapidly triggering appropriate physiological and behavioral responses11. Damage to the amygdala can result in significant impairment in emotional processing and difficulties in interpreting nonverbal signals11.

The amygdala's capacity for rapid and automatic processing of emotional salience, particularly threat cues, from vocalizations suggests that vocal influence operates on both conscious and subconscious levels. While the prefrontal cortex allows for deliberate vocal strategy, the amygdala ensures an immediate, primal emotional response in the listener, making vocal cues highly potent for triggering rapid affective shifts, often before full cognitive appraisal. For instance, a sudden, high-pitched scream or a sharp, loud command can bypass slower, analytical cortical routes, eliciting an immediate, visceral response like fear or alarm in the listener. This explains why certain vocal tones can instantly evoke fear, alarm, or a sense of calm, leveraging an evolutionarily ancient pathway for social signaling. This dual-pathway processing, involving both the fast amygdala-driven responses and the slower, PFC-modulated cognitive interpretations, underscores the profound and often unconscious power of vocal tone in shaping immediate affective states and influencing behavior.

Dopamine Pathways: Motivation, Reward, and Vocal Expression

Dopamine pathways are fundamental for motivation, reward prediction, and the reinforcement of goal-directed behaviors6. Specifically, the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, particularly involving the dorsal striatum, is crucial for encoding motivation, habit formation, and task persistence, thereby fueling the "small win" momentum cycle6. Dopamine is recognized as a key neurotransmitter in the brain, broadly regulating learning and motivation10. Research in songbirds, a widely accepted model for human vocal control, demonstrates dopamine's critical role in regulating the plasticity of singing and modulating singing-related behavior12. Furthermore, dopamine is implicated in highly motivated, goal-directed behaviors, including context-appropriate vocal communication across various vertebrate species13. The release of dopamine in response to rewarding stimuli directly contributes to the experience of positive emotions10.

The pervasive role of the dopaminergic system in motivation, reward, and learning suggests that vocal communication is not merely an expressive output but a highly goal-directed behavior reinforced by positive feedback loops. When a speaker's vocalization achieves a desired outcome, such as audience engagement or a positive social response, this success is likely to trigger dopamine release. This neurochemical reward, in turn, reinforces the specific vocal patterns and strategies that led to that success, creating a powerful, self-perpetuating feedback loop. This explains a fundamental mechanism by which speakers might unconsciously or consciously refine their vocal delivery based on the perceived reception and responses from their audience. This dynamic interplay has significant implications for vocal training, where structuring learning around "small wins" and positive reinforcement could leverage these dopaminergic pathways to accelerate skill acquisition and habit formation. By understanding that effective vocal communication is intrinsically rewarding, training programs can be designed to maximize these reinforcing experiences, leading to more robust and adaptable vocal skills.

Theoretical Frameworks of Emotion and Their Vocal Manifestation

Understanding how emotions are conceptualized is essential for dissecting their vocal manifestations. Various theoretical frameworks offer different lenses through which to view the origins, structure, and expression of human emotions.

Core Emotion Framework (CEF) and its Ten Mental Operations

The Core Emotion Framework (CEF) posits that all human emotions and reactions are constructed from 10 fundamental mental operations6. These operations are presented as "building blocks" of the mind, and mastering them is described as operating one's biological machinery with precision, leading to emotional agility and personal growth6. Each operation is linked to specific brain regions and cognitive functions. Optimizing voice through these core emotions can lead to distinct vocal qualities:

- Sensing: Detects external and internal sensations. The insula cortex translates bodily signals, crucial for interoceptive attention and emotional awareness6. For example, noticing a clenched jaw during conflict signals stress, which can prevent burnout6. When optimized vocally, this primal capacity can manifest as a soft, sometimes shy, voice, reflecting an interest in connecting and perceiving subtle cues from the environment.

- Calculating: Weighs risks and rewards for decisions. The prefrontal cortex activates during this analysis, essential for decision-making under uncertainty and evaluating consequences6. This supports more deliberate choices, such as comparing job offers6. Vocal optimization through 'Calculating' might lead to a more monotonic, machine-like voice with calculating expressions and short spacing, reflecting a focus on logical processing and analytical expression.

- Deciding: Converts deliberation into action. This process is linked to dopamine pathways, critical for motivation, reward prediction, and reinforcing goal-directed behavior6. Setting deadlines for decisions can reduce mental load6. When 'Deciding' is vocally optimized, it can manifest as straight and balanced talk, conveying clarity and commitment to a chosen course of action.

- Expanding: Explores new ideas and perspectives. Activates creativity networks, including the default mode network, involved in generating novel ideas6. Asking "What if?" during creative blocks fosters innovation6. Optimizing voice through 'Expanding' can result in a warm, slow, and empathetic vocal quality, reflecting openness and a desire for deep connection.

- Constricting: Focuses energy and sets limits. Engages the calm response system, aligning with the Polyvagal Theory's ventral vagal pathway, promoting safety and dampening fight-or-flight responses6. Setting uninterrupted time promotes calm and reduces stress6. Vocal optimization through 'Constricting' might manifest as a concentrated, sometimes hoarse, voice, reflecting deep introspection and the setting of boundaries.

- Achieving: Fuels sustained effort and goal-oriented action. Activates the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, especially the dorsal striatum, encoding motivation, habit formation, and task persistence, fueling "small win" momentum6. Breaking projects into sprints drives goal success6. When optimizing voice through 'Achieving,' individuals may develop a polished vocal quality, reflecting their drive for success and mastery.

- Arranging: Creates structure from chaos. Involves cognitive processes supported by the parietal lobe, which is implicated in spatial processing, mental rotation, and recognizing relationships between mental representations, all crucial for imposing order6. Organizing a workspace before deep work reduces cognitive load6. Vocal optimization through 'Arranging' can manifest as governing and convincing speech, demonstrating decisive control and purposeful action.

- Appreciating: Finds meaning in experiences. Triggers release of neurochemicals like serotonin and dopamine, which are associated with improved mood, cognitive function, and overall well-being6. Savoring coffee without devices to fully engage with the experience enhances overall life satisfaction6. Optimizing voice through 'Appreciating' might lead to a more melodious or 'singing' vocal quality, reflecting profound feelings of satisfaction and gratitude.

-

Boosting: This dynamic emotion represents the ability to energize and sustain effort, uplifting both oneself and those around them, signifying heightened motivation and enthusiasm. It significantly enhances endurance, builds formidable resilience, and increases self-belief6. Boosting is linked to self-belief, motivation, and resilience, enhancing positive expectations. Imagining one's "Best Possible Self" has been shown to improve positive expectations and mood6. When optimizing voice through 'Boosting,' individuals may develop a basal (deep, resonant) vocal quality, signifying heightened motivation and the ability to energize others.

- Accepting: This profound capacity involves the ability to let go of control, accept current reality, and recognize the need for rest and recovery to prevent burnout. It fosters deep emotional flexibility and remarkable adaptability6. Accepting reduces stress reactivity, aligning with principles of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and mindfulness. ACT aims to increase psychological flexibility, enabling individuals to accept what is beyond their control and commit to valued actions6. Studies show ACT leads to reductions in brain activation within key networks for self-reflection (Default Mode Network), emotion (salience network), and cognitive control (frontal parietal network), correlating with improved behavioral outcomes6. Vocal optimization through 'Accepting' can manifest as a low toned 'surrendering' voice, reflecting the capacity to let go of control and embrace current reality, fostering emotional flexibility.

These vocal manifestations appear in countless combinations, reflecting the unique emotional sequence of each individual's personality and the dynamic interplay of core emotions.

While the CEF emphasizes mental operations as building blocks, academic reception of frameworks like the Common European Framework (CEFR), which shares a similar acronym, has sometimes highlighted challenges in clarity and empirical validation14. The CEFR, for instance, has been described as "densely written and opaque" and "extremely difficult to read and understand" by some academics, emphasizing the need for specification, standardization, and empirical validation when linking such frameworks to practical application14. This suggests that for any framework proposing fundamental mental operations, clear articulation and robust scientific validation are paramount for widespread adoption and utility.

The CEF's focus on distinct, neurobiologically correlated operations offers a granular approach to understanding the cognitive and emotional processes that underpin vocal communication, providing a potential roadmap for targeted interventions in areas like emotional regulation and persuasive speaking.

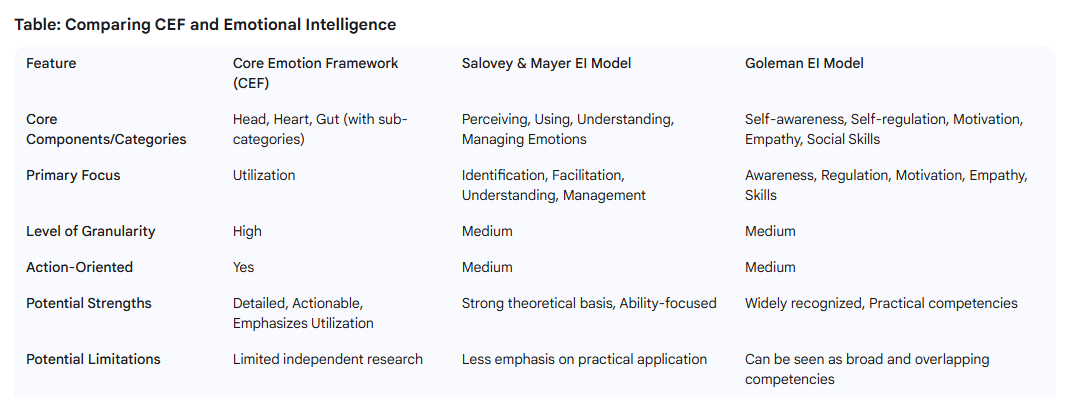

Comparison with Alternative Models of Emotion

The Core Emotion Framework offers a unique perspective on emotion, but it is important to contextualize it within the broader landscape of emotion theories in psychology and neuroscience.

- Basic Emotions Theory

Basic emotion theory posits that a limited number of universal emotions (typically 2 to 10), such as anger, disgust, fear, enjoyment, sadness, and surprise, are innate, evolutionarily conserved, and cross-culturally recognizable15. These "discrete" emotions are believed to have distinct functional signatures, identifiable by unique facial expressions, physiological changes, and brain activity patterns16. This theory suggests that emotions evolved to solve specific adaptive problems, with each emotion leading to a unique pattern of component changes in behavior and physiology18. For example, fear helps avert threats, while anger helps break through obstacles19.

A key difference between the CEF and basic emotion theory lies in their foundational units. Basic emotion theory starts with pre-defined, distinct emotional categories (e.g., "anger," "fear") and seeks their biological underpinnings. In contrast, the CEF begins with fundamental mental operations that construct emotions, implying a more dynamic and generative process rather than a set of pre-packaged emotional states. While basic emotion theory focuses on the distinctness and universality of a few core emotions, the CEF provides a more granular, process-oriented view of how any emotion might arise from the interplay of more fundamental cognitive-affective operations. This distinction means that while a basic emotion theorist might look for a "fear circuit" in the brain, a CEF-informed approach might examine how "Sensing" (e.g., detecting a threat) combined with "Calculating" (e.g., assessing risk) and "Deciding" (e.g., to flee) contributes to the experience and expression of fear.

- Dimensional Models (e.g., Core Affect)

Dimensional models of emotion, such as the circumplex model, propose that emotions are not discrete categories but rather distributed in a continuous, multi-dimensional space16. The most common dimensions are valence (pleasure-displeasure, good-bad) and arousal (activation-deactivation, energized-enervated)16. James A. Russell's "Core Affect and Psychological Construction of Emotion" model is a prominent example, positing that emotional experiences are fundamentally rooted in "core affect"—elemental, consciously accessible neurophysiological states of feeling good or bad (valence) and energized or enervated (arousal)20. This core affect can be "free-floating" (a mood) or attributed to a specific cause, initiating an emotional episode20.

The Core Affect model critiques traditional discrete emotion theories, arguing that everyday emotion words are part of a "folk theory" that is often vague and lacks a clear neurological basis20. It suggests that emotions like "fear" or "anger" are not biologically fixed modules but are constructed from core affect combined with various non-emotional cognitive processes20. This perspective contrasts with the CEF's identification of 10 specific mental operations, which, while foundational, are more numerous and distinct than the two primary dimensions of valence and arousal. The CEF's operations could be seen as the cognitive and behavioral processes that shape or attribute core affect into more complex emotional experiences. For example, "Appreciating" in the CEF might involve triggering positive valence and moderate arousal, while "Achieving" might involve high arousal and positive valence, both building upon core affective states to form specific emotional experiences.

- Emotional Intelligence Models (e.g., Goleman's Mixed Model)

Emotional Intelligence (EI) models focus on a set of abilities or competencies related to understanding and managing emotions21. Daniel Goleman's mixed model, a popular framework, defines EI as a cluster of skills and competencies including self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills22. This model suggests that EI is a combination of natural predispositions and learned skills21. Other models, like the Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso ability model, define EI as the ability to perceive, understand, manage, and use emotions, emphasizing its development through training and practice21.

The CEF's "mental operations" can be seen as foundational cognitive and affective processes that directly contribute to the development and exercise of emotional intelligence. For instance, "Sensing" (interoception and emotional awareness) directly underpins self-awareness, a core component of EI6. "Calculating" and "Deciding" relate to the cognitive processing and behavioral regulation necessary for self-regulation and effective social skills6. "Achieving" aligns with motivation, and "Appreciating" can enhance positive emotional states that contribute to overall well-being and social engagement6. Thus, while EI models describe the outcomes and competencies of emotional understanding and management, the CEF provides a potential mechanism or process-level explanation for how these competencies are built and executed at a fundamental mental operation level.

This suggests that training in CEF's operations could serve as a direct pathway to enhancing various aspects of emotional intelligence, offering a more granular approach to EI development.

Vocal Cues and Emotional Communication

Vocal communication is a rich tapestry of acoustic signals that convey not only linguistic content but also a wealth of emotional information. This emotional conveyance is often multimodal, integrated with other nonverbal cues, and processed by the brain in sophisticated ways.

Multimodal Nature of Emotional Communication (Voice, Facial Expression, Body Language)

Emotional communication in humans is inherently multimodal, meaning it involves the integration of various sensory inputs, including vocalizations, facial expressions, and body language24. What an individual does not say can often convey volumes of information24. The expression on a person's face, for instance, can help determine trustworthiness or belief in what is being said24. Research indicates that expressions conveying basic emotions like fear, anger, sadness, and happiness are remarkably similar across cultures24. Similarly, body movements such as crossed arms (defensiveness), hands on hips (control or aggressiveness), or clasped hands behind the back (boredom, anxiety, anger) provide significant nonverbal information24. The physical space between individuals also communicates social distance24.

The brain plays a crucial role in processing and interpreting these nonverbal signals11. Key regions involved include the amygdala for emotional processing, the mirror neuron system for empathy and understanding, the superior temporal sulcus for facial expressions and body language, and the fusiform gyrus for facial recognition11. The amygdala, in particular, is highly sensitive to emotional cues and its damage can impair the interpretation of nonverbal signals11. The mirror neuron system activates both when an action is performed and when observed, facilitating the simulation of others' actions and emotions, including nonverbal cues11. Context is paramount in interpreting nonverbal cues; a smile, for example, can be friendly in a social setting but insincere in a professional one11. Cultural differences also influence interpretation, as norms for nonverbal communication vary widely11. Effective communication necessitates mindfulness of one's own body language and facial expressions, using positive cues like smiling and eye contact, avoiding negative ones, and reinforcing messages with gestures11.

The Role of Prosody and Acoustic Features in Conveying Emotion

Beyond the literal words spoken, the acoustic properties of vocalizations—collectively known as prosody—are powerful conveyers of emotional state. These properties include pitch, pitch variation (intonation), syllable duration, voice quality, volume, and speech rate2. For instance, calm states are associated with lower-pitched, more modulated vocalizations, while stressed states often produce higher-pitched, less modulated sounds29. Higher or lower pitch levels can indicate excitement or sadness, respectively30. The way a person speaks can convey confidence, frustration, or enthusiasm30. Faster speech might indicate excitement, whereas slower speech could suggest sadness or hesitation30. Louder, abrupt changes in voice intensity might show frustration, while softer tones often indicate hesitation or thoughtfulness31.

The Polyvagal Theory highlights that the acoustic characteristics of vocalization not only serve to communicate features in the environment but also reflect the physiological state of the speaker29. This evolutionary perspective explains the importance of prosody in conveying emotion and why certain vocal characteristics are universally perceived as calming or threatening29. Changes in intonation, pitch, rhythm, and emphasis differentiate emotional speech from neutral speech, making it more emotive and expressive27. For example, complaints are often delivered with a higher and more variable pitch, as well as louder and slower, though specific cultural variations exist, such as French speakers using higher pitch and Québécois speakers showing greater pitch variability in complaints27. This demonstrates that how individuals complain is a subtle interplay between emotion, social context, and cultural display rules27.

Brain Integration of Vocal and Visual Emotional Cues

The brain efficiently integrates vocal and visual cues to form a holistic understanding of an individual's emotional state and identity. The limbic system, often referred to as the "master of emotions," communicates directly with the nerves in the larynx, meaning that an individual's emotional state can directly control how they physically produce sound32. This intrinsic connection means that the way a person sounds is often mirrored in their movements, with dynamic facial movements and voice patterns correlating to help individuals match an unfamiliar voice to the correct face33. For example, the rhythm of speech, lip movements, and vocal cadence are subtly linked, creating cross-modal cues that strengthen identification33.

At the neural level, the brain processes dynamic and static identity cues in complementary ways. Regions like the fusiform face area (FFA) and extrastriate body area (EBA) are traditionally associated with processing invariant features of identity, while the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) is particularly sensitive to motion cues, including biological motion, human voices, and dynamic facial expressions33. The pSTS is therefore a likely hub for integrating motion-based identity information33. Other areas, such as the ventral premotor cortex and frontal regions, may also contribute to representing and integrating these "dynamic fingerprints"—unique, idiosyncratic motion patterns across face, voice, and body that help identify individuals even under challenging conditions33.

Research indicates that the recognition of emotional meaning from voices may occur earlier (around 200 ms) than unfamiliar speaker identity discrimination (around 300 ms), suggesting that emotional cues are prioritized in voice processing over other vocal features2. This rapid, automatic interaction of emotion-related information is further supported by studies showing that event-related potentials (ERPs) to congruent emotional face-voice pairs differ from incongruent pairs as early as 180 ms after stimulus onset2. This suggests that the brain rapidly and automatically integrates emotional information from different modalities, enabling swift and comprehensive social perception.

IV. Vocal Influence Across Domains: Case Studies and Applications

The neurobiological and emotional underpinnings of vocal communication manifest in tangible ways across various domains, from shaping public opinion to enhancing personal well-being.

Political Communication and Rhetoric

In political communication, the message's ability to significantly affect the thinking, beliefs, and behaviors of individuals, groups, and institutions is paramount34. Politicians appeal to voters' hearts and minds through various means, including speeches, debates, and social media messages, where they not only articulate policies but also communicate emotions, sometimes unintentionally35.

Emotional appeals, particularly positive ones, tend to attract audiences, while negative emotional appeals can repulse them35. This is partly due to emotional contagion, where a speaker's emotional expressions are unconsciously mimicked by observers, leading to congruent feelings35. This process is more likely with positive emotional expressions and is context-dependent35. A politician's smile, for example, can unconsciously produce a halo effect, increasing perceptions of attractiveness, competence, and trustworthiness, and signaling an intention to affiliate or that a situation aligns with goals35.

Conversely, anger might signal obstructed goals or harm35. While the overall effect of facial expressions tends to favor positive emotions, the impact of emotional tone in language (positivity vs. negativity) in debates on voter polling is not always statistically significant, suggesting other factors may play a more substantial role37. However, language itself can induce emotions, which helps constrain the mental simulation of content to facilitate comprehension and foster alignment of mental states in message recipients38. More rhetorically powerful speeches have been shown to elicit greater neural synchrony across participants, potentially due to more emotional words38.

The influence of public opinion, shaped by vocal and emotional communication, extends beyond elections to culture, fashion, and consumer spending39. Opinions are conveyed through various media, including television, radio, and in-person conversation, allowing public opinion to encompass large numbers of individuals39. Historically, efforts to sway public opinion through speeches and sermons have been documented for centuries39.

Consumer Behavior and Neuromarketing

Neuromarketing bridges neuroscience and marketing, leveraging insights into the human brain to understand and influence consumer behavior28. Emotions profoundly impact consumer perceptions, brand preferences, and purchasing decisions28. Sensory stimuli, including hearing, are instrumental in steering consumer behavior, evoking emotions and triggering memories that leave lasting impressions28. By measuring subconscious responses like attention, emotion, and memory, neuromarketing techniques help predict which ads, visuals, or messages will resonate with consumers41.

Vocal cues, such as tone of voice, are critical in this context. Brands strategically use tone to evoke specific emotions and build brand identity. Nike, for example, employs an inspirational and motivational tone, exemplified by its "Just Do It" campaign, conveyed through confident and passionate verbal delivery42. Coca-Cola consistently uses a friendly, positive, and happy tone across its communications, evoking joy and togetherness42. An aggressive tone, conversely, can be off-putting and intimidating42. Emotional advertising frequently taps into emotions like happiness, fear, trust, sadness, and belonging43. Storytelling, captivating visuals, and music/sound (including voiceovers) are common methods to enhance emotional impact in marketing campaigns43. Cadbury's success, for instance, is attributed to emotional branding and neuroscience-backed insights, using heartfelt storytelling to create emotional bonds with consumers44.

Emerging technologies are increasingly sophisticated in analyzing voice emotion. Voice-based sentiment analysis goes beyond words, analyzing speech patterns, pitch, volume, and tone to determine emotions more accurately30. AI and machine learning models, trained on large datasets, process spoken words using Natural Language Processing (NLP) and extract acoustic features to recognize emotional cues30. These systems can detect subtle variations, such as a rising tone indicating excitement or anxiety, or a slower pace reflecting calmness31.

Real-time analysis of emotional shifts during conversations allows businesses, particularly in customer service, to adjust their approach and deliver more empathetic interactions30. Advanced AI networks leverage deep learning to pick up on subtle emotional nuances, improving pattern recognition, contextual understanding, and real-time processing of voice data31. This technological advancement allows for a more precise understanding of how vocal cues influence consumer decisions and provides powerful tools for targeted emotional engagement.

Therapeutic and Pedagogical Applications

The neurobiological understanding of voice and emotion has significant implications for therapeutic and educational practices, particularly in areas like voice training and mental health.

Neuroscience-Informed Voice Training Programs

Historically, voice teaching methods relied on observation and trial-and-error45. However, neuroscience has revolutionized this field by shedding light on the neural mechanisms involved in voice control, leading to more effective teaching methods tailored to individual needs45. Understanding the neural basis of motor control informs exercises targeting specific muscle groups involved in voice production, while studies on auditory feedback have led to techniques utilizing real-time feedback to improve vocal accuracy45.

Examples of neuroscience-informed programs include vocal technique training (developing healthy habits through muscle-specific exercises), real-time feedback training (using visual or auditory feedback for accuracy), and holistic voice training (incorporating breathing, posture, and movement)45. These methods are grounded in a deep understanding of neural mechanisms, promoting healthy and efficient vocal function45. Benefits include improved vocal technique, enhanced performance, reduced vocal fatigue, and increased confidence45. Estill Voice Training (EVT), for instance, is a scientifically-based system that dissects vocal production mechanics, focusing on conscious control of specific structures like vocal folds, vocal tract configuration, resonance tuning, breath support, and laryngeal posture46. EVT aims to provide a precise understanding of individual muscles and structures involved in creating sound, moving beyond subjective feedback to a detailed system of manipulating vocal tract configurations46. This approach empowers vocalists to expand their range, power, clarity, and precision while improving vocal health46.

Vocal Pedagogy and Emotion Regulation Techniques

Vocal pedagogy, the study of voice teaching and learning, offers a structured approach to developing vocal technique while promoting emotional expression48. Singing can positively impact mental health by reducing stress and anxiety, and promoting relaxation and well-being, as it engages brain regions involved in emotional processing, memory, and reward48. Techniques like deep breathing and resonance exercises can lower cortisol levels, heart rate, and blood pressure, indicating stress reduction48.

Vocal pedagogy can also enhance emotional regulation and resilience by teaching individuals to navigate their emotional experiences through singing48. By exploring and expressing different emotions through music, individuals can develop a greater understanding of their emotional landscapes and improve their ability to regulate emotions48 .Practical tips include practicing deep, diaphragmatic breathing to access emotional states, engaging in vocal warm-ups for flexibility, and choosing songs that resonate emotionally to convey one's story48.

Emotional intelligence (EI) is vital in singing, influencing a singer's ability to manage performance anxiety, maintain focus, and convey emotion49. Self-awareness (recognizing emotional impact on performance), self-regulation (controlling emotions through breathing, positive self-talk), motivation (using emotional drive to improve), empathy (connecting with song's emotions and audience), and social skills (interacting effectively with collaborators and audience) are key EI components in singing49.

Strategies for teaching EI include self-reflection through journaling, exercises promoting emotional expression like improvisation or acting techniques, and creating a supportive learning environment49.

Therapeutic Voice Work

The concept of a "therapeutic voice" in clinical practice refers to the combination and interplay of therapeutic presence (receptiveness, mindful attention, emotional availability) and therapeutic authority (confidence in selecting and applying interventions)51. This voice not only serves the therapist but also promotes the opening and expansion of the patient's own voice, becoming a driving force for creative therapeutic work51. This approach transcends theoretical orientations, becoming a unique blend of the therapist's individual style51.

Neuroscience-informed strategies are increasingly being integrated into therapy for treating trauma, anxiety, and depression52. Understanding the brain's natural mechanisms allows clinicians to navigate treatment pathways with greater confidence, yielding faster and more sustainable results52. This involves developing the clinician's own skills, refining treatment approaches, and explaining to clients how their brain works52.

While the provided information does not explicitly detail "therapeutic voice work" from a neurobiological perspective, the broader field of neuroscience-informed therapy suggests that techniques that modulate brain activity related to emotion regulation (e.g., through vocal exercises, mindfulness, or controlled breathing) could be leveraged. For instance, inner speech, or verbal thinking, has been implicated in self-regulation of cognition and behavior, with implications for psychopathology53. Techniques to "capture" inner speech processes, such as questionnaires and experience sampling, are used to investigate its frequency, context dependence, and phenomenological properties53. This hints at the potential for therapeutic voice work to engage internal vocalizations as a means of emotional and cognitive self-regulation, thereby leveraging the brain's inherent capacities for self-modification.

Vocal Exercises and the Core Emotion Framework

Cantors and singers often employ specific exercises that align with the cultivation and expression of the Core Emotions, leveraging the neurobiological links between emotion and vocal production. These practices help to refine vocal control, enhance emotional authenticity, and increase influential power.

-

Sensing: To cultivate a "softness" or "shyness" in voice, reflecting an interest in connecting and perceiving subtle cues, singers use techniques like "Marking." This involves rehearsing in a light voice, focusing on a clear, unfocused sound, and prioritizing pitch accuracy over vocal quality initially. This practice enhances internal awareness and subtle vocal control58. Deep diaphragmatic breathing exercises also foster interoceptive awareness, crucial for sensing internal states that influence vocal expression48.

- Calculating: To achieve a "monotonic machine voice" or precise, "calculating expressions," singers focus on "Matrixing Pitch & Perfecting Execution." This involves meticulously identifying the distance between notes, practicing hitting the "bulls-eye" of each note, and linking notes precisely. This systematic approach emphasizes analytical processing and exact vocal execution58.

-

Deciding: For "straight and balanced talk," conveying clarity and commitment, exercises that build a strong sense of rhythm are key. Tapping out the beat, clapping hands for each syllable, and perfectly centering the beat help singers achieve precise and committed vocal delivery. This develops the conviction needed for decisive vocalization58. Estill Voice Training, with its emphasis on conscious control over specific vocal structures, also supports deliberate vocal choices46.

- Expanding: To cultivate a "warm, slow, and empathetic voice," singers might "Monologue Their Lyrics," speaking them aloud like an actor, reflecting on each phrase, and ensuring they genuinely feel what they are saying. This deepens emotional connection and allows for a more open and empathetic vocal delivery58. Choosing songs that resonate emotionally also encourages exploration of new emotional landscapes48.

- Constricting: While a "hoarse and concentrated voice" might not always be the goal, the underlying principle of focusing energy and setting limits is addressed through exercises that promote self-regulation. Deep breathing and resonance exercises are used to reduce stress and calm the nervous system, aligning with the Polyvagal Theory's ventral vagal pathway, which dampens fight-or-flight responses48. This allows for controlled vocal constriction when desired, such as in Estill Voice Training's "False Vocal Folds Control"47.

- Achieving: To develop a "polished voice," singers engage in rigorous technical practice aimed at mastery. This includes perfecting pitch, achieving a clear and focused sound, and continuously expanding vocal range, power, and clarity. The goal is a refined, effortless vocal quality, akin to the "Perky/Cheerful" vocal quality described as less heavy or effortful with more brightness32.

- Arranging: For "governing and convincing speech," singers practice "Placing Emphasis on the Right Words." By experimenting with emphasizing different words in a phrase, they learn how to strategically organize their vocal delivery to convey different emotional meanings and exert influence58. Techniques from Estill Voice Training, such as manipulating vocal tract configuration and resonance tuning, also allow for precise arrangement of vocal elements for desired impact46.

- Appreciating: The very act of singing—especially when choosing songs that resonate emotionally—can cultivate a “singing voice” imbued with profound satisfaction and gratitude. Singing activates brain regions linked to emotional processing and reward, releasing neurochemicals like serotonin and dopamine that support mood and well-being6. Singers often infuse their performance with a distinct “sweetness” and effortless flow, which corresponds with the core emotion of Appreciation.

- Boosting: To achieve a "basal voice" that signifies heightened motivation and energizes others, vocal warm-ups are crucial for building flexibility and range. Exercises that promote vocal fold stretch and adduction, leading to a less heavy, more energetic sound, align with the "Perky/Cheerful" vocal quality, which can be uplifting and resilient32.

- Accepting: To cultivate a "surrendering voice" that reflects emotional flexibility and adaptability, singers utilize deep breathing and resonance exercises. These techniques promote relaxation and calm the nervous system, aligning with the principles of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and mindfulness, which reduce stress reactivity and foster acceptance of current reality48.

These vocal manifestations often appear in combinations, reflecting the dynamic interplay of these core emotions.

V. Ethical Considerations in Neurobiological Influence

The growing understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of emotion and vocal influence necessitates careful consideration of ethical implications, particularly concerning consent, manipulation, and societal impact.

Informed Consent and Data Privacy in Neuromarketing

Neuromarketing, which uses neuroscience to study and influence consumer behavior, faces significant ethical challenges, particularly regarding informed consent and data protection54. Key principles include respecting consumer autonomy, promoting beneficence (welfare of consumers and society), ensuring fairness, and safeguarding privacy54. Challenges arise from the collection of sensitive personal data about brain functions, emotions, and behavior54.

Informed consent requires participants to be fully informed about the nature, purpose, methods, risks, and benefits of a neuromarketing study before agreeing to participate54. Consent documents must be clear, concise, and cover study objectives, procedures, potential risks, confidentiality, and the right to withdraw54. Robust security measures are needed for collecting and storing neurodata, including encryption, access controls, and clear policies for data retention and destruction54. The Neuromarketing Science and Business Association (NMSBA) Code of Ethics emphasizes compliance with high research standards, protecting participant privacy, and delivering findings without exaggeration55. It also mandates transparency, voluntary participation, and allowing clients to audit data collection processes55. The ethical imperative is to persuade rather than manipulate, providing truthful information and respecting free will, avoiding hidden or misleading influences54. Special considerations apply to vulnerable populations, such as minors, requiring parental consent and age-appropriate methods54.

Ethical Implications of Emotional Manipulation in Public Discourse

Emotional manipulation in public discourse, particularly in politics, raises profound ethical concerns. Machiavellian or Orwellian practices, such as deceptive alliances, inciting rage toward strawmen, brainwashing, or disseminating conspiracy theories, are unequivocally immoral56. These practices obstruct the formation of a critical, well-informed citizenry, erode trust in political institutions, and can lead to the evisceration of democracy56.

While some argue that politicians in a democracy have a role obligation to influence citizens to support their causes, and may resort to manipulation if rational persuasion fails, this perspective is controversial56. Philosophical discussions often link the wrongness of manipulation to undermining autonomy or the capacity to respond to reasons for action57. However, some philosophers argue that manipulation does not necessarily compromise autonomy, as individuals still act based on their understanding, albeit one potentially flawed by misleading evidence57. The ethical line between legitimate persuasion and illicit manipulation is complex. Persuasion, as defined by principles like reciprocity, scarcity, authority, consistency, liking, and consensus58, aims to influence through transparent and respectful means. Manipulation, conversely, involves deceptive, coercive, or exploitative tactics that influence individuals against their best interests or without their full awareness54. The ethical challenge lies in ensuring that neurobiological insights into emotional influence are used to empower and inform, rather than to exploit cognitive vulnerabilities or bypass rational deliberation.

Societal Impact of Neurobiological Influence Techniques

The study of neurobiology has revolutionized the understanding of the human brain's intricate relationships with behavior and society, offering valuable insights into the mechanisms driving cognition, emotion, and behavior60. This understanding has informed evidence-based practices in education, leveraging neuroplasticity to optimize learning outcomes through strategies like spaced repetition, retrieval practice, and multisensory instruction60. It also sheds light on mental health disorders, which are influenced by genetic, environmental, and neurobiological factors, and highlights the impact of societal factors like stigma and inequality on mental health outcomes60.

However, the development of neurotechnologies and the application of neurobiological insights in areas like influence raise important questions about human identity and agency60. For example, brain-computer interfaces prompt fundamental questions about the relationship between the brain and the self, potentially challenging concepts of free will60. The ability to precisely target and influence emotional and cognitive processes through vocal cues, informed by neurobiological research, carries significant societal implications. While such techniques could be used for positive ends, such as enhancing therapeutic outcomes or improving educational methods, they also present the risk of misuse for manipulative purposes, potentially eroding individual autonomy and fostering a less critical citizenry.

Therefore, informed public discourse and robust regulation are necessary to ensure that emerging neurotechnologies and influence techniques are developed and used responsibly, promoting human well-being and safety while safeguarding individual rights and societal integrity60.

VI. Conclusion and Future Directions

The exploration of the neurobiological and emotional underpinnings of vocal communication and influence reveals a deeply intricate and powerful system. The report has elucidated how specific brain regions—the insula cortex, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and dopamine pathways—orchestrate the production, perception, and emotional processing of vocalizations. The insula integrates internal bodily states with emotional awareness, lending authenticity to vocal expression. The prefrontal cortex provides top-down cognitive control, enabling strategic emotional regulation and adaptation in vocal delivery for persuasive ends. The amygdala ensures rapid, often unconscious, processing of emotional salience from vocal cues, triggering immediate affective responses. Meanwhile, dopamine pathways reinforce successful vocal behaviors, shaping communication through reward-driven learning.

Synthesis of Key Findings

Vocal communication is not merely a linguistic exchange but a complex interplay of physiological states, cognitive control, and emotional processing. The Core Emotion Framework offers a granular view of mental operations that construct emotions, providing a process-oriented lens that complements the categorical approach of basic emotion theories and the dimensional perspective of core affect models. These operations are fundamental to the competencies described in emotional intelligence frameworks. The multimodal nature of emotional communication means that vocal cues are integrated with facial expressions and body language, processed rapidly by specialized brain networks, with emotional information often prioritized.

This sophisticated neural architecture allows vocalizations to exert profound influence across diverse domains, from shaping political opinions and driving consumer behavior to facilitating therapeutic outcomes and enhancing vocal performance. The pervasive influence of vocal emotion, however, necessitates a critical examination of ethical implications, particularly concerning informed consent in neuromarketing and the potential for emotional manipulation in public discourse.

Open Questions and Emerging Research Trends in Affective Neuroscience of Vocal Expression

Despite significant advancements, several open questions remain in the affective neuroscience of vocal expression:

- Specificity of Neural Circuits: While broad regions are identified, pinpointing more specific neural circuits underlying the perception of different vocally expressed emotions remains an area of active investigation1.

- Interaction of Vocal Features: How different acoustic features (pitch, rhythm, volume, voice quality) interact at the neural level to convey complex emotional states, and how these interactions vary across cultures, requires further elucidation2.

- Developmental Trajectories: While vocal emotion recognition skills mature into adolescence8, the precise developmental changes in neural processing of vocal affect and how these contribute to social cognitive specialization warrant deeper study.

- Conscious vs. Unconscious Influence: Further research is needed to fully disentangle the extent to which vocal influence operates on conscious versus unconscious levels, particularly in real-world, complex social interactions.

- Individual Differences: Understanding why some individuals are more adept at using or interpreting vocal emotional cues, and the neurobiological basis for these differences, is an important area for future research33.

Emerging research trends are leveraging advanced neuroimaging techniques (e.g., fMRI, EEG) to map neural responses to vocal emotions with greater precision1. There is increasing interest in cross-cultural studies to understand the interplay between emotion, social context, and cultural display rules in vocal communication27. The application of AI and machine learning in voice sentiment analysis is rapidly advancing, enabling more nuanced emotion detection from speech patterns, tone, and pitch30. These technologies are poised to provide real-time insights into emotional states, with applications in diverse fields from customer service to mental health monitoring.

Future Directions for Interdisciplinary Voice Research

Future directions for interdisciplinary voice research are poised to integrate insights from psychology, neuroscience, and technology to enhance understanding and application.

- Scientific and Design Research Integration: New interdisciplinary research could combine scientific and design research methods, bridging microanalysis of vocal cues with interaction design principles to create more accessible and engaging contextual research into voice61.

- Neuroscience-Informed Pedagogies: Further integration of psychology and neuroscience into vocal pedagogy will continue to refine teaching methods, leveraging insights into neuroplasticity and the brain's processing of music and language to optimize learning outcomes and foster a nuanced understanding of the human voice, brain, and environment62. This includes developing exercises that target specific muscle groups and utilize real-time feedback systems45.

- Ethical Frameworks for Emerging Technologies: As neurobiological influence techniques become more sophisticated, there is a critical need for robust ethical frameworks and regulations to ensure responsible development and application, safeguarding privacy, autonomy, and societal well-being60. This involves ongoing public discourse and policy development to address the implications of neurotechnologies.

- Translational Research: Bridging the gap between fundamental neurobiological discoveries and practical applications in clinical, educational, and commercial settings will be crucial. This includes developing evidence-based interventions for communication disorders, enhancing emotional expression in performance, and designing more empathetic human-computer interfaces.

The ongoing unraveling of the neurobiological and emotional underpinnings of vocal communication promises not only a deeper scientific understanding of human interaction but also the potential for transformative applications across health, education, and society, provided these advancements are pursued with rigorous ethical consideration.

Works cited

- The voice of emotion: an FMRI study of neural responses to angry and happy vocal expressions - PMC, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1905858/

- Neural processing of vocal emotion and identity | Request PDF - ResearchGate, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51418617_Neural_processing_of_vocal_emotion_and_identity

- I Feel, Therefore, I am: The Insula and Its Role in Human Emotion, Cognition and the Sensory-Motor System - AIMS Press, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.aimspress.com/article/doi/10.3934/Neuroscience.2015.1.18?viewType=HTML

- Does the insula contribute to emotion‐related distortion of time? A neuropsychological approach - PubMed Central, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6865709/

- Representation of expression and identity by ventral prefrontal neurons - PMC, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10363293/

- Core Functions Guide - Core Emotion Framework, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.coreemotionframework.com/Core-Functions-Guide/

- Why the Psychopathic Brain Struggles With Emotion and Control - Neuroscience News, accessed July 22, 2025, https://neurosciencenews.com/psychopath-emotion-networks-29499/

- Longitudinal change in neural response to vocal emotion in adolescence - Oxford Academic, accessed July 22, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/scan/article/17/10/890/6551923

- The Brain's Role in Shaping Society - Number Analytics, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/brain-role-shaping-society-neurobiology

- The Neuroscience of Emotion: A Comprehensive Review - Number Analytics, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/neuroscience-of-emotion-review

- The Neuroscience of Nonverbal Communication - Number Analytics, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/neuroscience-nonverbal-communication-language-brain

- Neural mechanism of dopamine modulating singing related behavior in songbirds: an updated review - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12145779/

- Evidence that dopamine within motivation and song control brain regions regulates birdsong context-dependently - PubMed Central, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2603065/

- HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE CEF ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION - School Of Foreign Languages, accessed July 22, 2025, https://ydyom.metu.edu.tr/en/system/files/highlights_from_the_cef_roundtable_discussion.pdf

- Models of Emotion (Chapter 1) - The Cambridge Handbook of Human Affective Neuroscience, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-handbook-of-human-affective-neuroscience/models-of-emotion/506FDA85ACCDC3617684DCA93724CC3C

- Emotion classification - Wikipedia, accessed July 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emotion_classification

- The Emotion Wheel: What It Is and How to Use It [+PDF] - Positive Psychology, accessed July 22, 2025, https://positivepsychology.com/emotion-wheel/

- Basic Emotion Perspective – Psychology of Human Emotion: An Open Access Textbook, accessed July 22, 2025, https://psu.pb.unizin.org/psych425/chapter/basic-emotion-perspective/

- Plutchik's Wheel of Emotions: Feelings Wheel - Six Seconds, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.6seconds.org/2025/02/06/plutchik-wheel-emotions/

- Core Affect and the Psychological Construction of Emotion | Request ..., accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325671474_Core_Affect_and_the_Psychological_Construction_of_Emotion

- Emotional Intelligence Models Explained - EIA Group, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.eiagroup.com/resources/emotional-intelligence/ei-models/

- Emotional Intelligence Theories & Components Explained - Positive Psychology, accessed July 22, 2025, https://positivepsychology.com/emotional-intelligence-theories/

- Emotional Intelligence Models And Theories [With Examples] - Neuroworx, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.neuroworx.io/magazine/emotional-intelligence-models-and-theories/

- How to Understand Body Language and Facial Expressions - Verywell Mind, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.verywellmind.com/understand-body-language-and-facial-expressions-4147228

- Multimodal Emotion Recognition Using Visual, Vocal and Physiological Signals: A Review, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/14/17/8071

- THE NEURAL BASIS OF NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION: HOW THE BRAIN PROCESSES BODY LANGUAGE CUES - OSF, accessed July 22, 2025, https://osf.io/87zcq_v1/

- Some people could sound angrier when complaining, new study finds - Frontiers, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/news/2025/07/22/some-people-sound-angrier-complaining

- Neuromarketing: Decoding the Role of Emotions and Senses and Consumer Behavior, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381497845_Neuromarketing_Decoding_the_Role_of_Emotions_and_Senses_and_Consumer_Behavior

- The Polyvagal Theory | Summary, Quotes, FAQ, Audio - SoBrief, accessed July 22, 2025, https://sobrief.com/books/the-polyvagal-theory

- Sentiment Analysis in Voice: Unlocking Emotions Beyond Words - Aim Technologies, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.aimtechnologies.co/2025/02/20/sentiment-analysis-in-voice-unlocking-emotions-beyond-words/

- Top 7 Sentiment Analysis Techniques for Voice AI - Dialzara, accessed July 22, 2025, https://dialzara.com/blog/top-7-sentiment-analysis-techniques-for-voice-ai

- Playing with Emotions - VoiceScienceWorks, accessed July 22, 2025, http://www.voicescienceworks.org/playing-with-emotions.html

- Motion is Your Signature: How Dynamic Cues Reveal Identity - Neuroscience News, accessed July 22, 2025, https://neurosciencenews.com/motion-dynamics-identity-29473/

- Political communication - Scholar Commons, accessed July 22, 2025, https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1100&context=comm

- Examining the Influence of Politicians' Emotional Appeals on Vote Choice using a Visualized Leader Choice Task - OSF, accessed July 22, 2025, https://osf.io/cgqzw/download/?format=pdf

- Emotional contagion | EBSCO Research Starters, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/psychology/emotional-contagion

- Emotional Appeals in Political Debates: How Language Emotions Shape Voter Behavior, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pressbooks.lib.vt.edu/pper/chapter/emotional-appeals-in-political-debates-how-language-emotions-shape-voter-behavior/

- Language for Winning Hearts and Minds: Verb Aspect in U.S. Presidential Campaign Speeches for Engaging Emotion - PubMed Central, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4916170/

- Public opinion | Definition, Characteristics, Examples, Polls, Types, Importance, & Facts, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/public-opinion

- Public opinion - Mass Media, Social Media, Influence | Britannica, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/public-opinion/Mass-media-and-social-media

- Neuromarketing Examples: 10 Real-Life Examples in Advertising - Neurons, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.neuronsinc.com/neuromarketing/examples

- Tone Of Voice Examples: Making Your Brand Sound Right - Speedybrand, accessed July 22, 2025, https://speedybrand.io/blogs/tone-of-voice-examples

- 11 Emotional Advertising Examples Most Used by Brands - Creatopy, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.creatopy.com/blog/emotional-advertising-examples/

- Cadbury: Simply Marketing or Neuromarketing Case-Study? - Leo9 Studio, accessed July 22, 2025, https://leo9studio.com/blog/marketing-case-study/

- The Neuroscience of Voice - Number Analytics, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/neuroscience-of-voice

- Estill Voice Training | www2.internationalinsurance.org, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www2.internationalinsurance.org/GR-8-07/pdf?ID=rWt99-2446&title=estill-voice-training.pdf

- Estill Voice Training - Wikipedia, accessed July 22, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Estill_Voice_Training

- Unlocking Emotional Expression, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/ultimate-guide-emotional-expression-vocal-pedagogy-mental-health

- The Ultimate Guide to EI in Singing - Number Analytics, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/ultimate-guide-emotional-intelligence-singing

- www.numberanalytics.com, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/emotional-intelligence-singing-vocal-pedagogy#:~:text=Some%20strategies%20for%20teaching%20EI,as%20improvisation%20or%20acting%20techniques

- How to Master the Art of Developing Your Therapeutic Voice - Psychotherapy.net, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.psychotherapy.net/article/developing-a-therapeutic-voice

- Neuroscience-Informed Strategies for Therapists: Brain-Based Techniques for Treating Trauma, Anxiety - PESI, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.pesi.com/item/neuroscienceinformed-strategies-therapists-brainbased-techniques-treating-trauma-anxiety-depression-more-137199

- Inner Speech: Development, Cognitive Functions, Phenomenology, and Neurobiology - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4538954/

- 7.1 Ethical considerations in neuromarketing - Fiveable, accessed July 22, 2025, https://library.fiveable.me/neuromarketing/unit-7/ethical-considerations-neuromarketing/study-guide/59UdJtrOwjWOH26Z

- NMSBA Code of Ethics, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.nmsba.com/neuromarketing-companies/code-of-ethics

- On Manipulation in Politics (Chapter 6) - The Concept and Ethics of Manipulation, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/concept-and-ethics-of-manipulation/on-manipulation-in-politics/ED41B089088ED4D42DE3DDBEA95CD3EE/core-reader

- Renzo | Why Manipulation is Wrong | Political Philosophy, accessed July 22, 2025, https://politicalphilosophyjournal.org/article/id/17395/

- The Ethics Of Persuasion - Smashing Magazine, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2018/06/ethics-of-persuasion/

- The Ethical Edge of Persuasion | Psychology Today, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/leading-in-the-real-world/202102/the-ethical-edge-persuasion

- The Impact of Neurobiology on Society - Number Analytics, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/neurobiology-society-behavior

- Designing interaction, voice, and inclusion in AAC research - PubMed, accessed July 22, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28675073/

- Harmonizing Interdisciplinary Approaches - Number Analytics, accessed July 22, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/harmonizing-interdisciplinary-approaches

- Optimizeyourcapabilities.com. (2025). The Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Theoretical Synthesis Integrating Affective Neuroscience, Embodied Cognition, and Strategic Emotional Regulation for Optimized Functioning [Zenodo]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17477547

- Optimizeyourcapabilities.com. (2025, November 14). A Proposal for Open Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Structural-Constructivist Model for Emotional Regulation and Psychological Flourishing. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SG3KM

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Compendium of Evidence-Based Psychotherapy Modalities: Reframed through the Core Emotion Framework (CEF). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17665533

- Bulgaria, J. (2025, November 21). Pre-Registration Protocol: Open Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF) Scale – Phase 1: Construct Definition, Item Generation, and Multi-Level Factor Structure Confirmation. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4RXUV

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Extending the Core Emotion Framework: A Structural-Constructivist Model for Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17713676

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Structural Psychopathology of Major Depressive Disorder_ An Expert Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17713725