Emotional Cycling in The Core Emotion Framework (CEF)

Are you ready to stop feeling overwhelmed by your emotions and start truly mastering them? Explore the Core Emotion Framework (CEF) which provides a revolutionary system to distill the vastness of human emotion into ten fundamental Core Emotions, This offers a clear, actionable map for inner growth.

Here is a groundbreaking new theory: Somatic Energetics of Emotion. This isn't about physical exercise, but about cultivating profound internal shifts by directing your mental and energetic focus within your Head, Heart, and Gut. Learn how to subtly cycle energy to enhance your "Sensing," find internal balance in your Heart to boost your "Performing," or direct a gentle rhythm in your Gut to deepen your "Appreciating." This is your invitation to unlock new dimensions of emotional intelligence and become the empowered architect of your inner world.

The Somatic Energetics of Emotion: A Novel Theory of Core Emotion Activation through Directed Internal Focus

This article introduces a novel, exploratory theory, "Somatic Energetics of Emotion," proposing that specific internal, directed mental or energetic movements linked to the body's energetic centers (Head, Heart, Gut) can directly influence the activation and balance of the ten Core Emotions as defined by the Core Emotion Framework (CEF). Drawing upon principles of mindfulness, embodied cognition, and internal energy work, this theory hypothesizes that conscious, internally visualized "cycling" or "swinging" within these centers can selectively stimulate or regulate distinct Core Emotions, offering a new, non-physical pathway for emotional optimization. This paper outlines the theoretical premise, proposes specific internal focus-emotion correlations, and issues a call for empirical validation through rigorous research.

Keywords: Core Emotion Framework, Somatic Energetics, Embodied Cognition, Emotional Regulation, Internal Focus, Mindfulness, Energy Psychology, Neuro-Emotional Connection.

exploring Tripartite three-directional cycling at the CEF

1. Introduction: The Embodied Nature of Emotion and Internal Power

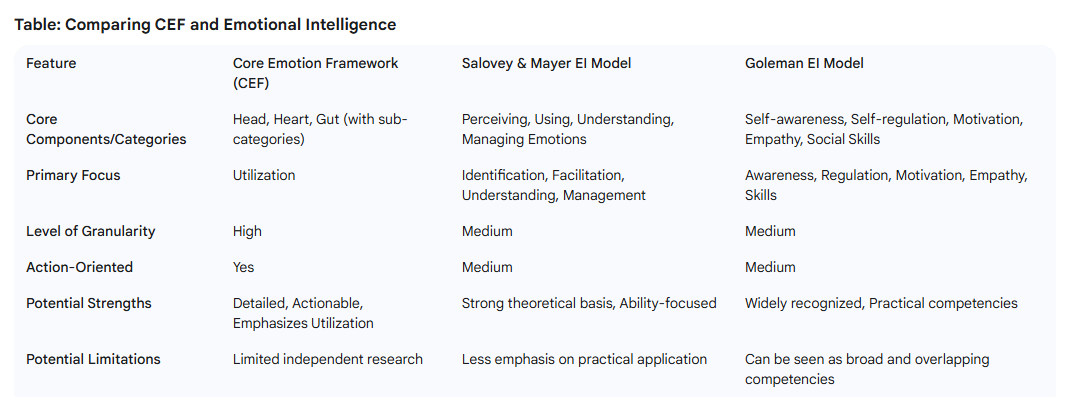

The Core Emotion Framework (CEF) postulates that human emotional experience is built upon ten fundamental, universal Core Emotions, each representing a distinct psychological capacity (Goleman, 1995; Bar-On & Parker, 2000; Optimize Your Capabilities, 2025). While the CEF has elucidated the conceptual "detanglement" and "stretching" of these emotions for enhanced well-being, the question of how to precisely and intuitively activate or balance these core states through direct, personal engagement remains a frontier.

This article presents a novel theoretical model: Somatic Energetics of Emotion. We propose that specific, intentional internal focus and energetic directionality, particularly when conceptualized as "cycling" or "swinging" motions within the body's energetic centers – the Head, Heart, and Gut – may directly influence the activation and flow of specific Core Emotions. This theory posits a subtle, yet profound, embodied pathway to emotional self-regulation, significantly extending the practical applications of the CEF.

While this theory is currently exploratory and awaits empirical validation, it draws inspiration from fields that recognize the deep connection between directed internal attention, the body's subtle energies, and mental-emotional states (e.g., mindfulness traditions, internal martial arts, energy psychology, and emerging concepts in embodied cognition).

Primary Purpose of Emotional Cycling

The core purpose of Emotional Cycling is to activate each center individually by awakening its three operators through movement. Cycling is performed on one center at a time, using three directional motions:

- Clockwise (CW) — activates the center’s Outgoing operator

- Counter‑Clockwise (CCW) — activates the Reflecting operator

- Swinging (Side‑to‑Side) — activates the Balancing operator

This center‑first method restores operator independence, strengthens underused functions, and prevents emotional fusion. Only after center‑level cycling is stable should advanced methods be explored.

Secondary / Advanced Cycling (Operator‑Level Cycling)

Once center‑level cycling is mastered, a more advanced method may be explored: cycling individual operators directly. This involves connecting to a single operator—such as Sensing, Calculating, Expanding, or Boosting—and cycling that operator itself through the three directional motions:

- Clockwise (CW) — activates the operator’s Outgoing expression

- Counter‑Clockwise (CCW) — activates the operator’s Reflecting expression

-

Swinging — activates the operator’s Balancing expression

This method is experimental and not yet fully investigated. Its purpose is to test operator independence, strengthen underused functions, and detangle fused emotional patterns. Operator‑level cycling should only be attempted after the user demonstrates clear activation of each center through primary cycling.

Experimental Cross‑Center Cycling (Tertiary Method)

After both center‑level and operator‑level cycling are stable, a third method may be explored: cross‑center cycling. This involves cycling one center and then transitioning into another, creating a directional flow across the emotional architecture.

Examples include:

- Head → Heart → Gut (Clockwise)

Supports rational integration and top‑down alignment.

- Gut → Heart → Head (Counter‑Clockwise)

Energizes the system and restores agency before returning to clarity.

- Heart ↔ Gut (Swinging Between Centers)

Trains relational grounding while maintaining motivation and surrender.

This method is highly advanced and not yet fully investigated. It is primarily used for research, emotional choreography, and testing the dynamic relationships between centers. It should only be attempted after the user demonstrates clear independence of all operators within each center.

2. Theoretical Foundations: Bridging Internal Awareness, Mind, and Emotion

The idea that directed internal attention and energetic focus can influence psychological states is central to many ancient wisdom traditions and is gaining traction in modern scientific inquiry. Mindfulness practices cultivate present-moment awareness, often directed internally to bodily sensations or breath, leading to profound emotional regulation (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). Embodied cognition extends this by suggesting that our internal bodily states and perceptions are not just outputs of cognition but actively shape it, meaning conscious internal focus could directly influence cognitive and emotional processing (Barsalou, 2008; Wilson, 2002).

Furthermore, energy psychology and various meditative practices emphasize the concept of subtle energy systems within the body (e.g., Qi, Prana, or simply bio-electric impulses). They propose that directing conscious attention or visualizing specific energy flows can impact mental and emotional well-being (Feinstein, 2010). Our novel contribution is to propose a direct, specific correlation between these internally directed "energetic movements" (conceptualized as clockwise, counter-clockwise cycles, or swings) within defined internal "power centers" and the activation of individual Core Emotions within the CEF framework. This offers a highly granular and actionable approach to subtle emotional self-mastery.

It is crucial to emphasize that "cycling" or "swinging" in this context refers to internal, focused attention and energetic intention, not gross physical movements of the head, heart region, or gut. The "power" in these centers refers to their hypothesized energetic or neurological influence, the precise nature of which requires further scientific investigation.

3. The Somatic Energetics of Core Emotion Activation: Directed Internal Focus

The theory hypothesizes three primary "power centers" – the Head, Heart, and Gut – each linked to a distinct cluster of Core Emotions. Within each center, specific directional internal focus or energetic visualization is proposed to activate particular Core Emotions.

3.1. Head Center: Cognitive & Decisional Core Emotions

The Head Center (encompassing the brain and skull, as a locus of thought and perception) is hypothesized to influence Core Emotions related to cognition, perception, and decision-making.

- Internal Clockwise Cycle: Directing focused internal attention to create a gentle, imagined clockwise energetic cycle within the head space is hypothesized to activate Sensing. This internal movement may facilitate a receptive, open state of awareness, enhancing visualization, intuition, and the ability to process information subtly and non-judgmentally (see related concepts in sensory awareness meditation and focused internal attention, e.g., Goleman, 1988 on attentional training).

- Internal Counter-Clockwise Cycle: Directing focused internal attention to create a gentle, imagined counter-clockwise energetic cycle within the head space is hypothesized to activate Calculating. This internal motion is proposed to stimulate analytical thought processes, logical sequencing, and strategic planning, potentially by enhancing internal mental clarity and problem-solving capacities (e.g., similar to how mental rotation tasks engage specific cognitive resources, Shepard & Metzler, 1971).

-

Internal Swinging Motion: Directing focused internal attention to create a subtle, imagined pendulum-like "swinging" or oscillation within the head space is hypothesized to activate Deciding/Realizing. This internal motion may foster the integration of diverse perspectives, reducing mental ambivalence and promoting a clear, decisive internal state ready for action, potentially by harmonizing internal cognitive processes that lead to resolution (e.g., related to self-regulation and intentionality, Mischel, 2014).

3.2. Heart Center: Connection & Action Core Emotions

The Heart Center (located in the chest, associated with emotional connection, vitality, and empathy) is hypothesized to influence Core Emotions related to interpersonal dynamics, personal growth, and purposeful action.

- Internal Clockwise Cycle (Right Side Emphasis): Directing focused internal attention to create a gentle, imagined clockwise energetic cycle within the right side of the chest/heart region is hypothesized to activate Expanding. This internal movement may foster feelings of openness, compassion, generosity, and an internal drive for growth and connection, potentially influencing autonomic nervous system balance linked to prosocial states (e.g., related to compassion meditation and its physiological correlates, Lutz et al., 2008).

- Internal Counter-Clockwise Cycle (Left Side Emphasis): Directing focused internal attention to create a gentle, imagined counter-clockwise energetic cycle within the left side of the chest/heart region is hypothesized to activate Constricting. This internal motion is proposed to aid in internal boundary setting, focused self-preservation, and the disciplined containment of energy or emotion. It facilitates the ability to direct one's energy inward, promoting self-regulation and a sense of internal strength against external overstimulation (e.g., related to self-control and internal regulation, Heatherton & Wagner, 2011).

- Internal Balancing Motion: Directing focused internal attention to create a subtle, imagined "balancing" or centering motion within the core of the heart center is hypothesized to activate Achieving/Performing. This internal motion may cultivate an integrated sense of purpose, internal alignment, and readiness for effective action, fostering a state of focused determination that supports goal actualization (e.g., related to intentionality and mental rehearsal techniques, Taylor & Schneider, 1992).

3.3. Gut Center: Instinctual & Grounding Core Emotions

The Gut Center (located in the abdominal region, often associated with intuition, visceral sensation, and foundational stability) is hypothesized to influence Core Emotions related to organization, appreciation, and personal grounding.

- Internal Clockwise Cycle: Directing focused internal attention to create a gentle, imagined clockwise energetic cycle within the abdominal region is hypothesized to activate Arranging/Organizing. This internal movement may promote a sense of order, internal structure, and clarity, potentially influencing the deep intuitive processes and the gut-brain axis's role in psychological well-being and visceral knowing (e.g., similar to abdominal breathing and its calming, organizing effects, Ma et al., 2017).

- Internal Counter-Clockwise Cycle: Directing focused internal attention to create a gentle, imagined counter-clockwise energetic cycle within the abdominal region is hypothesized to activate Appreciating/Enjoying/Clapping. This internal motion is proposed to stimulate profound feelings of joy, contentment, and gratitude, potentially by influencing the complex interplay of neurotransmitters and internal sensations linked to positive affect and visceral pleasure (e.g., related to the role of gut microbiome in mood regulation, e.g., Yano et al., 2015). The "clapping" element suggests an internal sense of effervescent appreciation ready for expression.

-

Internal Swinging Motion: Directing focused internal attention to create a deliberate, imagined "swinging" or rhythmic oscillation within the gut center is hypothesized to activate Boosting/Grounding. This internal motion may enhance feelings of profound stability, inner presence, and vital energetic activation, supporting both robust energetic reserves and a deep, rooted sense of self. This aligns with internal energy practices that emphasize core engagement for stability and vitality (e.g., the cultivation of internal 'Qi' or 'Prana' through focused abdominal attention, Kuan, 1996; Lad, 1984).

-

Relaxation Techniques: Lying down, slow breathing, and releasing muscle tension are simple methods to cultivate the emotions of acceptance and surrender. Mindfulness and emotional release practices often highlight these techniques. For example, mindful breathing and body relaxation are foundational in fostering acceptance and surrender in emotional well-being (Raugh et al. 2025).

4. Proposed Mechanisms and Integration with CEF

The "Somatic Energetics of Emotion" theory posits that these internally directed mental/energetic movements may act as a sophisticated form of internal biofeedback. By consciously directing attention and intention to specific internal "power centers" and visualizing directional energy flows, individuals may create subtle neurological and physiological shifts that, through intricate mind-body pathways, directly influence the activation states of the corresponding Core Emotions. This could involve:

-

Enhanced Interoception: Sharpening the internal sense of the body, feeding nuanced information back to the brain (Craig, 2002).

- Autonomic Nervous System Modulation: Influencing the balance between sympathetic (activation) and parasympathetic (calming) responses, which are intimately linked to emotional states (Porges, 2007).

-

Neural Pathway Activation: Repeated, intentional internal focus may strengthen specific neural circuits associated with the targeted emotional states (Lutz et al., 2009).

- Energetic Synchronization: While more speculative, the internal movements might create a subtle energetic resonance, influencing the body's bio-energetic field and emotional experience (Feinstein, 2010).

Within the Core Emotion Framework, this theory offers a novel, active, and highly accessible modality for "stretching" and "detangling" Core Emotions. For an individual struggling to activate "Sensing" (e.g., feeling creatively blocked or unable to perceive subtle cues), consciously performing the internal clockwise cycle within the head could be a direct, non-physical intervention. Similarly, for someone experiencing an entangled "Calculating" and "Appreciating," specific internal directional foci might help disentangle these states, promoting a more fluid and balanced emotional experience. This provides a direct, intuitive, and highly personal method for the self-regulation and optimization that the CEF promotes.

5. Future Directions and Call for Research

The "Somatic Energetics of Emotion" theory is currently a conceptual framework designed to stimulate discussion and practical exploration. While anecdotal self-reports and initial personal experimentation may offer valuable insights, rigorous empirical validation is crucial to substantiate these claims. We propose the following avenues for future research:

- Phenomenological Studies: In-depth qualitative research to explore the subjective experiences of individuals practicing these internal energetic movements and their reported emotional shifts.

- Neurophysiological Correlates: Utilizing advanced neuroimaging techniques (e.g., fMRI, EEG) to observe specific brain activity patterns during these internal practices and correlate them with hypothesized Core Emotion activation.

- Autonomic Biomarkers: Measuring physiological responses (e.g., heart rate variability, skin conductance, electrodermal activity) to assess subtle autonomic nervous system modulation influenced by directed internal focus.

- Randomized Controlled Trials: Designing studies to compare the efficacy of these internal practices against control groups or other emotional regulation techniques for specific emotional outcomes.

- Mechanism-Based Research: Investigating the precise mind-body pathways through which these internal intentional movements might exert their influence.

6. Conclusion: A New Frontier in Internal Emotional Mastery

The "Somatic Energetics of Emotion" theory represents a bold step towards an integrated understanding of our internal landscape and its profound connection to our emotional states. By proposing direct, actionable connections between subtle internal focus and fundamental Core Emotions, it offers a potentially revolutionary pathway for self-regulation and optimization within the Core Emotion Framework. This exploratory model invites both personal, mindful experimentation and rigorous scientific inquiry, promising to unlock new dimensions of emotional intelligence and profound inner mastery.

References:

Academic References:

- Angelakis, I., Niarchou, A. P., & Papageorgiou, C. (2022). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 8, 100318.

- Bar-On, R., & Parker, J. D. A. (Eds.). (2000). The handbook of emotional intelligence: Theory, development, assessment, and application at home, school, and in the workplace. Jossey-Bass.

- Barsalou, L. W. (2008). Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 617-645.

- Comtois, K. A., Elwood, L., & Smith, C. C. (2007). The use of dialectical behavior therapy for the treatment of borderline personality disorder in an outpatient setting. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(12), 1163-1175.

- Craig, A. D. (2002). How do you feel? Interoception: The sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(8), 655-666.

- Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(10), 701-712.

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135-168.

- Elliott, R., Watson, J. C., Greenberg, L. S., & Auszra, L. (2004). Learning emotion-focused therapy: The process-experiential approach to change. American Psychological Association.

- Feinstein, D. (2010). Energy psychology: A review of the evidence. Psychological Topics, 19(2), 271-303.

- Fordham, M. A., & Williams, K. (2021). Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and cultural sensitivity. In Counseling and psychotherapy with diverse clients: A handbook for multicultural practice (pp. 201-218). Routledge.

- Goleman, D. (1988). The meditating mind: The varieties of meditative experience. Jeremy P. Tarcher.

- Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. Bantam Books.

- Greenberg, L. S. (2017). Emotion-focused therapy. American Psychological Association.

- Greenberg, L. S., & Johnson, S. M. (1988). Emotionally focused therapy for couples. Guilford Press.

- Greenwald, R. (2007). EMDR in the treatment of children and adolescents. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Harned, M. S. (2013). Trauma-informed dialectical behavior therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(10), 1085-1092.

- Heatherton, T. F., & Wagner, D. D. (2011). Cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation failure. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(3), 132-139.

- Jha, A. P., Krompinger, J., & Baime, M. J. (2007). Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(2), 109-119.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Delta.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144-156.

- Kliem, S., Klotsche, J., & Brähler, E. (2010). Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in patients with borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychiatric Quarterly, 81(4), 319-331.

- Kuan, K. L. (1996). The practice of qigong. Weatherhill.

- Lad, V. (1984). Ayurveda: The science of self-healing. Lotus Press.

- Levine, P. A. (2010). In an unspoken voice: How the body releases trauma and restores goodness. North Atlantic Books.

- Long, T., & Miller, R. S. (2004). The energetics of healing. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Lutz, A., Brefczynski-Lewis, J., Johnstone, T., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Regulation of the neural circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: Effects of expertise. PLoS One, 3(3), e1897.

- Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2009). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(4), 163-169.

- Lynch, T. R., Chapman, A. L., Rosenthal, M. Z., Kuo, J. R., & Linehan, M. M. (2007). Mechanisms of change in dialectical behavior therapy: Theoretical and empirical observations. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(12), 1083-1099.

- Ma, X., Yue, Z. Q., Gong, Z. Q., Zhang, H., Daimiel, I., & Li, R. H. (2017). The effect of diaphragm breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(8), 1017-1025.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Mischel, W. (2014). The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-Control. Little, Brown and Company.

- Moyers, T. B., Manuel, J. K., & Ernst, D. (2014). Motivational interviewing. In D. Wedding & M. P. Corsini (Eds.), Current psychotherapies (10th ed., pp. 315-348). Brooks/Cole.

- Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Paris, J. (2010). Is dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder the panacea? Journal of Personality Disorders, 24(3), 324-334.

- Porges, S. W. (2007). The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 116-143.

- Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2018). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse in recurrent depression (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Shapiro, F. (2017). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Shepard, R. N., & Metzler, J. (1971). Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects. Science, 171(3972), 701-703.

- Siegel, D. J. (2007). The mindful brain: Reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Swales, M. A., & Heard, H. L. (2009). Dialectical behavior therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge.

- Taylor, J., & Schneider, R. (1992). The athlete's guide to sport psychology: Mental training for peak performance. Leisure Press.

- Teasdale, J. D., Segal, Z. V., & Williams, J. M. G. (2000). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: An approach to preventing relapse in recurrent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 615-625.

- The Oxford Handbook of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. (2021). In J. T. Bunting & M. W. Bates (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Oxford University Press.

- van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

- Values in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. (2021). In J. T. Bunting & M. W. Bates (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Oxford University Press.

- Waltman, S. H., O'Leary, K. D., & Wilson, G. T. (2016). Critiques of cognitive behavioral therapy: Strengths and weaknesses. In The Oxford handbook of personality and social psychology (pp. 573-596). Oxford University Press.

- Wilson, M. (2002). Six views of embodied cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9(4), 625-635.

- Yano, J. M., Yu, K., Donaldson, G. P., Shastri, G. G., Hsiao, P. Y., Matson, S. K., ... & Mazmanian, S. K. (2015). Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell, 161(2), 264-276.

- Raugh, I. M., Berglund, A. M., & Strauss, G. P. (2025). Implementation of Mindfulness-Based Emotion Regulation Strategies: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis | Affective Science, 6, 171–200.

Websites:

- Optimize Your Capabilities. (2025). Core Emotion Framework: The Concept. https://www.optimizeyourcapabilities.com/the-background-basis-of-the-core-emotion-method/

- Core Energetics by Find the Path Core website.

-

Core Energetics. https://www.jeannedenney.com/core-energetics-somatic

-

Core Energetics Entry from the SAGE Encyclopedia. https://coreenergetics.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Core-Energetics-Entry-from-the-SAGE-Encyclopedia.pdf

-

Heart Centered Connection. https://www.integrativehaven.com/blog/heart-centered-connection

-

The Heart-Mind Connection. https://liveayurprana.com/blogs/windows-to-wellness/the-heart-mind-connection-how-emotions-impact-your-cardiovascular-health

-

The Instinctual Centre. https://lyckowbackman.se/enneagram/the-instinctual-centre-being-grounding-and-moving/

-

Enneagram Explained. https://enneagramexplained.com/enneagram-centers-of-intelligence/

-

Somatic Therapy Partners. https://somatictherapypartners.com/somatic-therapy-science-mind-body-connection-2025

-

Somatic Therapy: Healing Trauma Through Body-Mind Connection. https://neurolaunch.com/somatic-therapy-for-healing-trauma/

-

Optimizeyourcapabilities.com. (2025). The Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Theoretical Synthesis Integrating Affective Neuroscience, Embodied Cognition, and Strategic Emotional Regulation for Optimized Functioning [Zenodo]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17477547

-

Optimizeyourcapabilities.com. (2025, November 14). A Proposal for Open Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Structural-Constructivist Model for Emotional Regulation and Psychological Flourishing. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/SG3KM

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Compendium of Evidence-Based Psychotherapy Modalities: Reframed through the Core Emotion Framework (CEF). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17665533

- Bulgaria, J. (2025, November 21). Pre-Registration Protocol: Open Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF) Scale – Phase 1: Construct Definition, Item Generation, and Multi-Level Factor Structure Confirmation. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/4RXUV

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). The Core Emotion Framework (CEF): A Structural-Constructivist Model for Emotional Regulation and Adaptive Resilience in the Treatment of Anxiety. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17693163

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Extending the Core Emotion Framework: A Structural-Constructivist Model for Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder (OCD). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17713676

- Bulgaria, J. (2025). Structural Psychopathology of Major Depressive Disorder_ An Expert Validation of the Core Emotion Framework (CEF). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17713725

- Bulgaria, J. (2026). Bundle 4 — Unified CEF Emotional‑Technology Architecture [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18379695

The Cycling Protocol

Somatic Energetics: Directed Internal Focus for Core Emotion Activation

1. Theoretical Premise

The Cycling Protocol (Somatic Energetics of Emotion) hypothesizes that specific internal, directed mental movements within the body's three energetic centers—Head, Heart, and Gut—can selectively stimulate or regulate individual Core Emotions. This is a non-physical, visualized pathway to emotional mastery.

2. The Activation Matrix

(Cognition)

(Connection)

(Action)

3. Application Guidelines

- Subtlety over Force: Movements are visualized as gentle energetic rhythms, not physical strain.

- Intentionality: The goal is to "unlock" a specific functional capacity (e.g., using a counter-clockwise Head cycle to ignite analytical Calculating during complex tasks).

- Synchronization: Cycling acts as a balancing intervention for "entangled" or "blocked" emotional states.